Yes, I am ranting. Rant, rant, rant.

And I’ll tell you why. Because of the internet.

Because it makes me crazy and because so many misstatements of fact, so many bare-faced lies, and so much misinformed drivel is trotted out as fact on all the various blogs that clot up the blogosphere that it makes me absobloominglutely crazy.

So there I was today, reading along in my quaint little Englishey fashion, when I came upon a blog about George Brummell–or Beau Brummell, if you prefer. Whatever.

So there I was today, reading along in my quaint little Englishey fashion, when I came upon a blog about George Brummell–or Beau Brummell, if you prefer. Whatever.

And within two paragraphs, I was swearing. Expleting. Using the full-force of my extensive vocabulary in three languages!

(It’s at times like this that I hate being an expert. I hate, hate, hate it. I want to be a nice person, you see. I want to be supportive and lovely and charming and say things like, “That’s utterly fab!” and “I think you’ve done a smashing job…”

I do not, not, not want to be known as that wild-eyed, wilder-haired semi-lunatic professor who throws chalk [hard] with unerring accuracy at his students and hits them smack in the forehead when they get their Latin verbs wrong! [I had a professor like that once. He was utterly brilliant. Terrifying. But brilliant.])

Also, please understand that I don’t really have an interest in Brummell one way or another. I mean, I know lots about the fellow, because I read and research bloody everything, but knowing about him doesn’t get me firing on all cylinders like say the Russian light cavalry or formation of the Landwehr in 1813 does, or anything. I mean, I’m sure he was perfectly delightful but…

Also, please understand that I don’t really have an interest in Brummell one way or another. I mean, I know lots about the fellow, because I read and research bloody everything, but knowing about him doesn’t get me firing on all cylinders like say the Russian light cavalry or formation of the Landwehr in 1813 does, or anything. I mean, I’m sure he was perfectly delightful but…

But, okay, back to this blog…Because the first thing that set my teeth on edge was a bit about Brummell going to Eton where he ‘got to rub shoulders with the aristocracy’ as if it’s some sort of rare privilege accorded to a special few and we should all genuflect or something.

So let me be perfectly clear here: I am friends with several members of the aristocracy. Get over it.

In fact, until her death, my very dearest friend in all the world had a title–an ancient one. And do you know what? She was brilliant. She was smashing. She was the very least up-herself, stand-on-ceremony, proud or arrogant person in the entire world. And I loved her dearly. And I miss her like stink.

But I’ll tell you something else. She had to brush her teeth. Just like everyone else. And when she didn’t, she got cavities. Just like everyone else.

But back to Brummell.

The thing about that statement–besides the obvious aristophilia issue which has me splenetically croaking–is that the author had just finished telling us that Brummell was born at 10 Downing Street where his father lived because he was the private secretary to Lord North. Who was the Prime Minister under George III. And who had, clearly, a title.

And in and out of the front door of Downing Street, handing Billy Brummell (young George’s father) the requisite sweeteners to ensure that they could get in to see the Prime Minister were half the aristocratic heads in the kingdom. Because that’s how politics worked in those days.

So, young George would have been ‘rubbing shoulders’ with the aristocracy from the day he was born–or any time he wasn’t in the nursery…

Okay. (Breathing in. Breathing out.) So then I skipped a bit, because there wasn’t a wall close enough at hand against which I could bang my head. Hard…

And then I came across the statement that the thingie that’s called a Bow-window is called that because Beau Brummell used to sit in White’s bow window overlooking St. James’s Street. What?

Has no one but me heard of that superlative set of volumes known as the Oxford English Dictionary???? The repository of all the most wonderful information and the definitive authority on how and when words came into use in English? And there’s no bally excuse for not using it because it’s now ON-LINE!

And had the author of this blog bothered to check any of her facts in that fine and noble work, she would know that it was Samuel Richardson who first used the word ‘bow-window’ in print in the year 1753.

That’s 25 years before George Brummell made his appearance in Downing Street as a squalling brat.

Later, Repton uses in in a discourse on gardens and conservatories or something. And Austen used it in 1816 in Emma. It had nothing to do with Brummell or his soubriquet.

[I have–since yesterday–refered to the index in my copy of Ian Kelly’s biography, Beau Brummell, The Ultimate Dandy, and have found that Kelly does indeed refer to this thrice between pages 245-46. He writes: “The facade of White’s clubhouse…was remodelled during the second half of the eighteenth century, and a little later a bay window was added over a former doorway that became a landmark on St. James’s Street. Here Brummell held court in the afternoons, in a bow window that became known as the Beau Window…The men of the Dandiacal Body…’mustered in force’ around Brummel’s chair in the Beau Window, watching the world go by and telling jokes.” I, therefore, stand corrected on this point.]

Pause for more of that breathing manoeuvre…

So then, I skipped along and discovered the startling information that [allegedly] Brummell contracted the syphilis from which he died in 1840 in the last years of the 18th century, when he was stationed in Brighton with the Prince’s own 10th Regiment of Light Dragoons.

So then, I skipped along and discovered the startling information that [allegedly] Brummell contracted the syphilis from which he died in 1840 in the last years of the 18th century, when he was stationed in Brighton with the Prince’s own 10th Regiment of Light Dragoons.

Hello?

The only problem with that bijou fact-ette is that it’s impossible–which she would have known had the author bothered to read the whole of the Kelly biography that she cited in her footnotes.

Because syphilis was a fast-working killer in those days and as Brummell was clearly suffering the torments of tertiary syphilis in the 1820s and 30’s, he had to have contracted the disease in London, at the height of his fame and popularity. So around 1811.

Because by 1816, he’d shaved off his hair to combat the baldness that was a side-effect of the mercury treatment.

Had he contracted the disease in Brighton before 1797 as she averred, he would have been bald and losing his teeth by 1803–the very time he was introducing the starched cravat of folded linen to the gentlemen of White’s Club!

And the thing that really vexes me and peeves me in all this is that now this blog with all this rot is out there. You know? And some perfectly charming little person, having read a Georgette Heyer novel or something, will think, “Oooh Beau Brummell, I should google him…”

But instead of coming across a piece that will enlighten her and give her an insight into the early 19th century mindset and provide some useful historical context, instead of all that, this charming little person will get regurgitated sancitmonious Victorian de-sexualising b*ll*cks.

Because that’s what happened! By the time Gronow and his mateys were writing this pap about Brummell, Victoria was on the throne, Wellington–another quite the virile man about town–was a staid, elderly statesman, and all that naughty Regency stuff had to be white-washed–and for heaven’s sake, no one mention Harriette Wilson (Brummell’s close confidante and Wellington’s former mistress). And to say they messed with their facts doesn’t even get warm!

Because that’s what happened! By the time Gronow and his mateys were writing this pap about Brummell, Victoria was on the throne, Wellington–another quite the virile man about town–was a staid, elderly statesman, and all that naughty Regency stuff had to be white-washed–and for heaven’s sake, no one mention Harriette Wilson (Brummell’s close confidante and Wellington’s former mistress). And to say they messed with their facts doesn’t even get warm!

The very worst I ever read of that stuff was one late Victorian biog of Brummell which simpered on about his mincing walk which was like he was tiptoeing around the raindrops.

Ya, right. A chappie who was a cavalry officer–think boots, well-built shoulders, hard-drinking, hard-swearing, hard-riding, manly man, a fellow who spent 4-5 hours in the saddle every day–is supposed to have tippy-toed around the raindrops. I don’t think so.

Oh–and another thing. Brummell broke his nose when meeting face-to-face with a cobblestone. On account of his horse having shied and spooked.

Ehem.

I also have met with the ground, nose to nose, as it were, pretty much in the same way. Fortunately, it wasn’t a cobblestone, it was a hummock on the South Downs, so my nose does not have an interesting tilt to one side. However…It’s not Romantic. It’s just what happens…

And I’d also like to add that that prissy little picture of him isn’t Brummell. The most likely candidate for an accurate picture of him is this one with the broken nose…

And I’d also like to add that that prissy little picture of him isn’t Brummell. The most likely candidate for an accurate picture of him is this one with the broken nose…

So what was Brummell then, if he wasn’t this prissy sissy clothes-horse?

He was a man’s man. A very well educated man who wrote rather spiffing epigrams in Latin (most Eton boys did so–they’d been writing plays in Latin or Greek since they were about 14.) He loved dogs. And dogs loved him. He didn’t wear perfume or scented after-shave–he said a man should smell like clean, country-washed linen and nothing else.

And he most especially loved fabric. Not in a girlie kind of way–but more in the way I conjecture someone like Karl Lagerfeld or Yves St. Laurent loves fabric. He loved the weaves. He was passionate about the depth of colour in a good English wool. He loved how the cut of a coat could show off the fabric.

And the early 19th century was a great time for English wool–the new mechanised looms were producing some fantastic weaves and blends…and he loved them all. They set him alight. And his enthusiasm for the cut of the fabric and for the design that would emphasise that changed English menswear forever.

He was a dandy when the word didn’t mean some bloke who wears all different colours at one go and has floppy hair.

A dandy as he lived it [dandy in those days was defined as the opposite of a bore–work that out…] wore perfect tailoring in subtle and dark colours–dark blue or dark green jackets with buff coloured breeches for daytime and for evening black breeches (later pantaloons) with a well-cut black or navy coat. All of which sounds very contemporary, very button-down, very elegant. No?

Oh, and he had a great sense of humour–and played lots of practical jokes. A lot like Oscar Wilde from what I can tell…

He was seriously addicted to gambling. Compulsively. Obsessively. And it was this which destroyed him. He gambled away millions. And his addiction destroyed all his relationships–just as any addiction if left untreated will do–obliterated all other interests. It left the friends who lent him money to pay off his debts seriously up against it.

And in the end, he had no choice but to face the bailiffs or scarper off to Calais. Which is what he chose to do. In disgrace and ignominy.

As for this other stuff, well…I think what I need to say is, People, do your research. Do it properly. Check everything. Don’t present yourself as an expert if you’re not. And don’t even think about blagging it.

If only because I’m sick of knocking my head against the wall because you can’t be bothered.

Otherwise, shut the **** up.

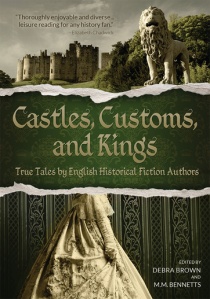

It hits the shelves on the 23rd September 2013, this tome does, courtesy of Madison Street Publishing.

It hits the shelves on the 23rd September 2013, this tome does, courtesy of Madison Street Publishing. “This book is a scholarly treasure trove with a wide appeal. It covers everything from the first English word to the food (and recipes) served at a Tudor feast. If you are interested in nonfiction works on England, history, and/or royalty you will find a book that you will return to. Fans of historical fiction and England will find the book rich in supplemental information to complement their reading with an introduction to authors of works they might enjoy.”

“This book is a scholarly treasure trove with a wide appeal. It covers everything from the first English word to the food (and recipes) served at a Tudor feast. If you are interested in nonfiction works on England, history, and/or royalty you will find a book that you will return to. Fans of historical fiction and England will find the book rich in supplemental information to complement their reading with an introduction to authors of works they might enjoy.”