This may come as a bit of a shock to some people, but despite having a reputation as a military firebrand of an historian and author, actually I began life as a social historian.

Which possibly sounds a bit girlie and light-minded. Until I tell you that under that heading I studied things like rural poverty, child mortality, changes in legislation, taxation, wages, the price of wheat, land-use, laws governing apprenticeships, nutrition, that kind of thing.

(I know, you cannot conceive of anything more boring. You thought, when I said social historian, it was going to be about society and cravats and banquets cooked by Careme with goldfish swimming in the ice sculpture centrepieces. Er, no. Not exactly.)

And as I was focusing at that time on the 15th century, my hero was the greatest demographer of the 20th century, Fernand Braudel. His epic works, Capitalism and Material Life and the three volumes of The Wheels of Commerce were my favourite texts. (Stop yawning.)

Anyway, I was reminded of all this recently when I was writing a post for another blog about landscape gardens in the 18th century.

Because as I put it all together, I realised that, for the most part, when people look at any novel which speaks of the landed gentry–such as Pride & Prejudice’s Mr. Darcy–or even when they visit a stately home here in the UK, there is little idea that the 18th century estate was a self-contained organic entity of agricultural industry.

For in the main, in our industrialised, urban society, we just don’t know what an estate was. Or beyond looking pretty and impressing the neighbours–how it functioned nor what it accomplished. We don’t even know what to look at in order to see it properly or as they would have done.

So when an estate is written about, it’s largely as a tablecloth setting for some story, proof that the owner had lots of dosh. And not much else. The workings (and the owner’s work) are unseen, unknown and uninvestigated.

So let’s start at the beginning.

When you look at estates, the big houses and the land or huge tracts of land surrounding them, including the landscaped gardens closest to the house, what you need to see is not just Nature wearing her best frock, but profitability and income.

Yes, the houses looked ravishing set amidst those glorious landscapes. But even as these houses were sat there, radiating the aura of grandeur, influence and wealth which is certainly what they were intended for, they were equally the nerve-centres of their own individual communities and industry.

Yes, the houses looked ravishing set amidst those glorious landscapes. But even as these houses were sat there, radiating the aura of grandeur, influence and wealth which is certainly what they were intended for, they were equally the nerve-centres of their own individual communities and industry.

Think about it.

Often these estates are several or even many miles from the nearest town–this is particularly true in the counties and shires farthest from London. There were no cars. No lorries. No trains. So whatever was needed by that estate’s community had to be available there, on the spot.

So, if it’s daily dairy products–milk, cream, butter, cheese–there will need to be cows, a dairy, dairymaids, perhaps a cowman or three…

If there’s going to be daily exercise for the family, that too has to be provided within the confines of what is readily available.

There is nowhere else for the families in these big houses to go for entertainment or exercise, or even perhaps for food. They must be self-sufficient. They are their own entertainment. They may invite guests for a week or a month to vary the interpersonal relationships, but they’re on their own for the most part.

There is nowhere else for the families in these big houses to go for entertainment or exercise, or even perhaps for food. They must be self-sufficient. They are their own entertainment. They may invite guests for a week or a month to vary the interpersonal relationships, but they’re on their own for the most part.

So, for example, for the landowner and his family, who can’t nip off to the gym because the nearest thing to a gym is twenty miles away, riding the estate’s land becomes not only a great joy–they loved their horses and they loved riding as do many people today. But it’s also good exercise, it gets one out of the house, and it’s a way of keeping track of the state of affairs, of their fences and fields.

Driving their carriages around the estate roads–ditto. Walking…another good option.

So too, an estate undoubtedly has one or more large kitchen gardens and an orchard too, to provide fresh produce for the table–both for the family and the servants. They’re very keen on this, having just discovered that fresh vegetables and fruit are the cure for scurvy. But this also means there are of necessity several gardeners working and living on the estate.

And then there’s the surrounding acreage.

In England, land is king. And unlike on the Continent where they have court centres such as Versailles, English landowners are fiercely devoted to the land and to their rural enterprises and for centuries the Tudors and Stuart monarchs have encouraged them so to be.

Remember too, that unlike on the Continent, particularly during the Seven Years’ War and Napoleonic Wars, there is no invading armed threat to the security of one’s land or property, no threat of ruination or pillage by marauding troops…So there’s stability. And this is key.

But land doesn’t manage itself. Nor do farms left unattended produce their own crops.

Now, there are two significant types of great landowners in the 18th century–the aristocratic Whig grandees who pretty much spend their time running the country, but who are rather less hands-on in regards to their estates, and the vast majority of Tory land-owning gentry, who are very hands-on.

(Mr. Darcy, given what his housekeeper says about him being the best landlord and the best master, etc. is probably the latter. Likewise Mr Knightley, with his intimate knowledge of his tenants and concern for their welfare.)

And over the course of the 18th century, as these people seek to expand their estates and their political influence, more and more land was enclosed as these landowners consolidated and extended their holdings through Acts of Enclosure–in layman’s terms, removed land from common or communal use. Even roads or hamlets came under this change.

And over the course of the 18th century, as these people seek to expand their estates and their political influence, more and more land was enclosed as these landowners consolidated and extended their holdings through Acts of Enclosure–in layman’s terms, removed land from common or communal use. Even roads or hamlets came under this change.

Before 1760, the rate of enclosures did not exceed 400,000 acres. While over the next forty years, some 21 million acres were enclosed by statute.

(And if you’re thinking that’s an awful lot of land, and probably the smaller, poorer farmers lost out in all this, you’re right.)

Then too, the late 18th century was an era of substantial improvement in agricultural practice–much of it led by Thomas Coke of Holkham, in Norfolk.

Between the years of 1778 and 1793, he transformed his Norfolk holdings to the extent that the income of his estate grew from £5000 to £20,000 a year, mainly through his innovation of double-digging the underlying marl and spreading it over the sandy topsoil–and this process converted the land from heath to fertile cornfields.

His work fascinated the landowners of Britain and they copied his improvements and constantly applied to him for advice on what they should do. Like I say, they were hands-on. (George III was a frequent correspondent of Coke’s on matters agricultural…)

Subsequently then, as recent studies have shown, the landowners acquired more land, they used the land to its best ability, managing it as part of the home farm. Or letting it out most often for grazing or mowing.

Chiefly because the rents from pasture were so much higher than the rents or income from arable land–the rate being as much as 50% greater for grazing than tillage. (Which is a tremendous yield for any farmer watching his pennies.)

The income from pasture is steadier too, and less dependent on the weather–which given the mini-Ice Age which was holding forth at the end of the 18th century was no bad thing. There were several bad harvests in the early years of the 19th century–the worst being 1811, when England had been forced to buy corn from enemy France.

But sheep are relatively unaffected by the weather–and the price of wool continued to hold steady–making them a safer farming bet. They’re also multi-purpose–there’s the wool and then there’s the meat. Cattle and deer are also less troublesome and prone to destruction by a fierce rainstorm or a late frost.

But sheep are relatively unaffected by the weather–and the price of wool continued to hold steady–making them a safer farming bet. They’re also multi-purpose–there’s the wool and then there’s the meat. Cattle and deer are also less troublesome and prone to destruction by a fierce rainstorm or a late frost.

And this wholehearted engagement with the world of agriculture goes all the way to the top of society too.

I’ve mentioned George III already. But Viscount Castlereagh’s letters to his father are full of his efforts to improve his herd of merino sheep at his farm in North Cray–you might have thought that being the Foreign Secretary he had more exciting things to discuss…but you’d be wrong.

Another vital element of the profitable estate was the production of timber.

Yes, the woodlands you see when you look out upon a landscaped park look lush and beautiful.

But most of the larger estates coppiced their vast woodlands and had their own sawmills (without the benefit of electric saws) which fed the constant demand for more and more lumber in the growing British economy. Whether for shipbuilding for the Royal Navy or the merchant marine, or for housebuilding or furniture building.

But most of the larger estates coppiced their vast woodlands and had their own sawmills (without the benefit of electric saws) which fed the constant demand for more and more lumber in the growing British economy. Whether for shipbuilding for the Royal Navy or the merchant marine, or for housebuilding or furniture building.

Because you see, on an estate, everything is part of everything else. The whole must work together in carefully managed harmony, and most things are multi-purpose.

So the woodlands served other purposes too. They provided excellent cover for pheasant–which in turn fed the family after a good day’s shooting in the autumn. And the woods usually had rides cut through them for the daily ride of the owner or his family, friends and visitors…(And the pheasants could usually be counted on to spook the horses, making for a little equestrian excitement. Ha ha ha.)

Thus a stand of trees in the distance might provide a focal point for the panoramic vista as seen from the house, but it might shroud a cowman’s outbuildings, the pheasants raised by hand live amongst the trees, and one could have a riproaring zig-zag of a path cut through the wood for those who like their rides invigorating and perhaps a little edgy…

At the head of this business proposition then, this small world of agriculture and forestry, is the landowner himself. The boss.

Yes, he collects rents which contribute to his income. Yes, he sells the timber to the shipyards which again provides his income. But when you weigh that in with his outgoings–keeping those big houses sound (and those tenants’ cottages too) with the roofs intact, meals on the table for himself, his family and all his staff, wages for his cowmen, his gardeners, his hands at the sawmill, his indoor servants…

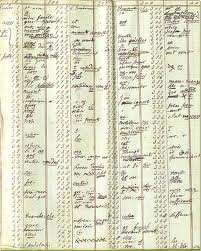

Suddenly it looks like this chappie (call him Mr. Darcy if you like) is the head of a major agricultural venture, busily totting up how to keep afloat through the long years of war with the French (when taxes were very high, and income tax was first introduced), discussing the price of corn with his land agent or whether they should drain that field at Dander’s Bottom and use it as further pasture, worrying that rain will spoil the harvest and then they’ll all have a rough year ahead, assessing whether this year’s dry spring will indeed make for a good apple harvest and thus a good pressing of cider which will last the winter, and will he still manage to get away for a couple of weeks to Cornwall with his sister…

Suddenly it looks like this chappie (call him Mr. Darcy if you like) is the head of a major agricultural venture, busily totting up how to keep afloat through the long years of war with the French (when taxes were very high, and income tax was first introduced), discussing the price of corn with his land agent or whether they should drain that field at Dander’s Bottom and use it as further pasture, worrying that rain will spoil the harvest and then they’ll all have a rough year ahead, assessing whether this year’s dry spring will indeed make for a good apple harvest and thus a good pressing of cider which will last the winter, and will he still manage to get away for a couple of weeks to Cornwall with his sister…

Oh, and the storm last week damaged the thatched roofs down on the tenants’ farms…and brought that old elm down right across Mrs. Baseley’s front doorstep.

Which brings me to my final and perhaps my most important point. When the elm came down, it was the landowner and his agent, not Mrs Baseley, who would make good the damage.

With our urban viewpoint and a century of socialist history influencing us, it’s too easy to see the estate–and there are many who would like to force us to see it this way–as part of an iniquitous and unjust class system.

Yes, there were some bad landowners who treated their tenants and servants poorly and couldn’t farm for toffee. But they were in the minority. Frankly because the income of a badly managed property will hardly support the lavish lifestyle. Or not for long. And those who were bad landlords generally couldn’t hang on to their lands. There’s also the inconvenient fact that managing a great estate properly is just too much constant hard work.

The great estates were not only whole communities but also the big local employers. They provided the livelihood and the stability for both the landowner and a vast army of workers–tenant farmers, gardeners, cowmen, sawyers and shepherds alike. (As well as providing employment for seasonal labourers like codders, harvesters, shearers…)

The great estates were not only whole communities but also the big local employers. They provided the livelihood and the stability for both the landowner and a vast army of workers–tenant farmers, gardeners, cowmen, sawyers and shepherds alike. (As well as providing employment for seasonal labourers like codders, harvesters, shearers…)

So the well-being of the landowner was inevitably and always bound up in the well-being of his staff, tenants and servants. (It’s no coincidence that Britain never experienced the kind of mindless and bloody class warfare of the French Revolution.)

And there was at base, in all their eyes, a sense of sanctity when they looked upon the acres and Downlands of “this sceptre’d Isle…this other Eden, demi-paradise…this blessed plot, this earth…this dear dear land…”

This is therefore what they saw. And it’s the reality of what Mr. Darcy and his father knew and lived.

And in this book which was set at a time when horses were the only means of transportation, we had our hero, who was meant to be a tall lanky fellow over 6′ tall, riding a little mare who, according to the author, was just over 14 hands. And our hero was so entranced by her that he hoped the dragoons wouldn’t steal her for their own.

And in this book which was set at a time when horses were the only means of transportation, we had our hero, who was meant to be a tall lanky fellow over 6′ tall, riding a little mare who, according to the author, was just over 14 hands. And our hero was so entranced by her that he hoped the dragoons wouldn’t steal her for their own. So according to our aforementioned novelist, his 6′ hero was riding a horse which stood 4’10” or so at the withers. So in fact our hero was towering over this poor little pony is what he was actually doing. And if you think that it would be good for a little ponio’s back to have a great lug of 6 foot on his back–no matter how lightly the chap rode–you should think again.

So according to our aforementioned novelist, his 6′ hero was riding a horse which stood 4’10” or so at the withers. So in fact our hero was towering over this poor little pony is what he was actually doing. And if you think that it would be good for a little ponio’s back to have a great lug of 6 foot on his back–no matter how lightly the chap rode–you should think again. Now, whinnying is a bit of an individual thing with horses. Some do. Others almost never do. But for the most part, they don’t do it much. They’re actually very quiet animals. They don’t draw attention to themselves for the benefit of prey animals by saying, “Hey Lion-face, here I am…aren’t you hungry?”

Now, whinnying is a bit of an individual thing with horses. Some do. Others almost never do. But for the most part, they don’t do it much. They’re actually very quiet animals. They don’t draw attention to themselves for the benefit of prey animals by saying, “Hey Lion-face, here I am…aren’t you hungry?”