There are a lot of armchair historians out there these days…which, don’t get me wrong, I think is a good thing.

For one thing, it may mean that the publishers who seem to have given up on publishing history in favour of celebrity drool-fests might rethink their strategy and go back to publishing works by the likes of Charles Esdaile, Dominic Lieven, Andrew Roberts, Michael Broers and all these other fabulous authors I admire. And that wouldn’t just be a good thing, it would be a grand and noble and enriching thing.

(It would additionally mean I’d have to add another bookcase in the Growlery, but who’s counting…)

Yet it often also means another thing, and that is, everybody’s got an opinion on everything. No matter how small, somebody’s going to give it to you when your views don’t match theirs.

Let me give you an example. Let’s consider the introduction of the waltz into British society. (A dangerous pastime, I know…)

You might think it’s of no import, and quite possibly, you’d be right. Does it matter? Did it lead to anyone’s death, to an epidemic of disease, to the cure of a disease, to war, to peace, to the emancipation of women or slaves? And the answer is, of course, none of the above. Nevertheless, a lot of folks get very miffy over it–insisting that it could not ever, ever, ever be mentioned in a book that was set earlier than 1815-1816.

And this is where the issue begins to impinge on self. Because my works (thus far) are set in 1812 and 1813…and I do mention the waltz. (And being a bit of a fiend for accuracy in my own work, this concerned me…)

And this is where the issue begins to impinge on self. Because my works (thus far) are set in 1812 and 1813…and I do mention the waltz. (And being a bit of a fiend for accuracy in my own work, this concerned me…)

So I was chatting about this dilemma to another historian, one whom I respect enormously as much for her knowledge as for her ability to approach problems from different angles.

And after recounting the adamant position of those who held that it was unknown here until the Lievens introduced it in the late autumn of 1812 (he was the Russian ambassador), and discussing with her the various historical references I had to hand, including engravings of waltzing couples published well before 1812, she said something quite interesting.

She said, “When was waltz music first published here? Because if they’re waltzing to music, then somebody has to be playing it for them…And that will tell you when it started to become popular and socially acceptable.”

Is that a stroke of genius or what? Of course, she’s right.

And it was at that point that things started to get very interesting. Because the first publication of music for the waltz was in 1806. A not-well-known-to-us English composer, Edward Jones, published A Selection of Original German Waltzes, and dedicated the volume of music to none other than the Princess Charlotte (who was only ten at the time).

And here’s another thing, publishing companies don’t just publish stuff for no reason–they have to believe there’s a market for their product and they’re going to sell the stock. So, 1806 has to herald enough of a degree of popularity for the music and dance that the sheet music is going to fly off the shelves…

Anyway, this novel approach to searching out the music led me to a number of quite fascinating bijou fact-ettes about the waltz, all of which kind of overturn the idea that this ‘shocking’ dance erupted on the scene out of nowhere in about 1814-15.

In 1810, Gillray published his famous caricature of waltzing couples, entitled, Le bon Genre.

There’s Lord Byron’s poem about it, A Satire on Waltzing, which was written in the autumn of 1812 and published anonymously in the spring of 1813. He disapproved, as unlikely as that seems, given his reputation:

Endearing Waltz! — to thy more melting tune

Bow Irish jig and ancient rigadoon.

Scotch reels, avaunt! and country-dance, forego

Your future claims to each fantastic toe!

Waltz — Waltz alone — both legs and arms demands,

Liberal of feet, and lavish of her hands;

Hands which may freely range in public sight

Where ne’er before — but — pray “put out the light.”

Methinks the glare of yonder chandelier

Shines much too far — or I am much too near;

And true, though strange — Waltz whispers this remark,

“My slippery steps are safest in the dark!”

There’s also the small matter of a letter from Lady Caroline Lamb, again written in 1812, which says:

There’s also the small matter of a letter from Lady Caroline Lamb, again written in 1812, which says:

“My cousin Hartington wanted to have waltzes and quadrilles; and at Devonshire House it could not be allowed, so we had them in the great drawing-room at Whitehall. All the ‘bon ton’ assembled there continually. There was nothing so fashionable.”

Equally, there is another private letter, this time by Byron, written in 1811, in which he complains about the immorality of the dance (yes, I know, rich coming from him!) and how all the nobility are indulging in it…

And finally, there’s this lovely bit of insight into Viscount Castlereagh’s personality–that’s the Foreign Secretary, in case you’d forgot, with the wife who’s allegedly a stodgy great stickler for manners and morals as well as a Patroness of Almack’s.

Nevertheless, by 1815, because he loved it so much, there was even a waltz dedicated to him, with the title, Lord Castlereagh’s Waltz. And the most famous dancing master of the age, Thomas Wilson, supplied not one, but two versions of this dance in his immensely popular volume, Le Sylph, An Elegant Collection of Twenty Four Country Dances published in 1815.

Nevertheless, by 1815, because he loved it so much, there was even a waltz dedicated to him, with the title, Lord Castlereagh’s Waltz. And the most famous dancing master of the age, Thomas Wilson, supplied not one, but two versions of this dance in his immensely popular volume, Le Sylph, An Elegant Collection of Twenty Four Country Dances published in 1815.

And years later, writing about her uncle’s fondness for the dance, Castlereagh’s beloved niece, Emma, would say:

“He liked the society of young people, and far from checking their mirth and their nonsense, he enjoyed and encouraged it, with his own fun and cheerfulness…he was able to work serenely at the most important dispatches amidst the clamour of a family party, which he preferred to the isolation of his study. If an air were played that pleased him, he would go to the pianoforte and sing it; if a waltz, he would say, ‘Emma, let us take a turn,’ and after waltzing for a few minutes, he would resume his writing. His power of abstraction was indeed remarkable; our talking and laughter did not disturb him; once only do I recollect that he rose from his chair laughing, and saying, ‘You are too much.’”

All of which evidence suggests to me that the waltz–not the one we know (and I’ll get to that in a minute)–was well and truly a fixture on the dance floor long before it was allowed at Almack’s.

Though even that date has to be fixed no later than June 1814, because Tsar Alexander was here for a few weeks’ visit then, and we know he loved to waltz (whether it was that he loved the dance or he loved the opportunity to get handsy, I can’t tell you), but I just can’t see anyone saying “no” to him–not even at Almack’s, where he assuredly went.

Which led me to examine the issue even more closely…one reference I found to it in 1802, spoke of the waltz as but one of a medley of elements making up the series of country dances…so lots of people were learning it and dancing it, they just didn’t necessarily have a separate designation for it.

It was at this point then, that I began to wonder, ‘Exactly, what the heck were they doing back then, really…

Eventually, I fossicked out the answer on the website of a dance historian by the name of Walter Nelson, who paraphrasing the description from the aforementioned book by Thomas Wilson, writes:

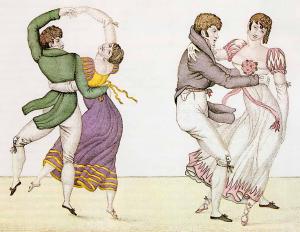

“It began with the ‘March’ which was a very brief side by side promenade. This turned quickly into the ‘Pirouette” or ‘Slow Waltz’. The partners would take each other in one of several holds, one of the more popular of which had the partners facing in opposite directions, hip to hip, with one arm across the front of the partner’s body and the other hands holding in an arch above the body. In this posture, they would rotate very slowly, with their gaze fixed on one another. This was the part that probably made the blue stockings the most nervous.

“It began with the ‘March’ which was a very brief side by side promenade. This turned quickly into the ‘Pirouette” or ‘Slow Waltz’. The partners would take each other in one of several holds, one of the more popular of which had the partners facing in opposite directions, hip to hip, with one arm across the front of the partner’s body and the other hands holding in an arch above the body. In this posture, they would rotate very slowly, with their gaze fixed on one another. This was the part that probably made the blue stockings the most nervous.

“The next was the ‘Sauteuse’. At this point, the dance got a bit more energetic, with the music tempo increasing and the dancers working a little hop into the step. The posture would be changed – one possible option would be the man holding both the lady’s hands behind her back.

The routine would finish with the ‘Jetté’ which was even more energetic and up tempo.”

And as Mr. Nelson also says of it:

“The Waltz we know today was not the Waltz of the Empire/Regency era. It was not the fast moving, twirling Viennese Waltz of the Victorians, and it was not the sedate but graceful box-step of the 20th Century. It was a strikingly intimate and sensuous dance, which is a major departure from the group dances and stately minuets of earlier generations. To a society that focused so much attention on harnessing teenage libido to the purpose of making a good marriage, this was rather disturbing.”

Wow!

So there you have it. It wasn’t as I thought. It wasn’t what anyone I’d spoken to previously thought. It was a twisty, turning tale of some were, some weren’t, some knew, some didn’t, here a little, there not so much…just like all history, really.

Not at all clear-cut…In fact, messy as a pig’s breakfast.

It can be hard to imagine, but there was a time when Beethoven’s music was unknown, or the newest, most daring thing one could imagine. And that time was 1812. His take on the sonata form was so different, so explosive when compared to what else was available, that we can hardly imagine the shock it must have occasionally caused.

It can be hard to imagine, but there was a time when Beethoven’s music was unknown, or the newest, most daring thing one could imagine. And that time was 1812. His take on the sonata form was so different, so explosive when compared to what else was available, that we can hardly imagine the shock it must have occasionally caused.