The primary factor in researching and writing the characters for a novel set in the early 19th century must be to look past the Victorian attempts to minimise the achievements of this age in order to maximise their own grandeur. So, in the main, I’ve often worked from primary sources–diaries, letters, journals and newspaper reports.

The primary factor in researching and writing the characters for a novel set in the early 19th century must be to look past the Victorian attempts to minimise the achievements of this age in order to maximise their own grandeur. So, in the main, I’ve often worked from primary sources–diaries, letters, journals and newspaper reports.

And as I have done so, I have to say, my respect and admiration for the men of this era has grown exponentially.

Pitt, Grenville, Castlereagh, Liverpool, Perceval–none of these men who served in high office during this period were experts at anything, except perhaps the Classics, or the Greats as they would have called them, which they studied at school and then at Oxford or Cambridge. Hence they could speak, read and write fluently in Latin and Classical Greek, though generally not in French or German.

None were financial wizards or spin doctors par excellence (the words fiscal and financial weren’t even in use yet); they had no special advisors, nor any particular expertise. They were none of them military strategists–hadn’t gone to West Point or Sandhurst.

There wasn’t a civil service. If they had a secretary, they themselves paid his salary.

They did their business not just in their offices, but as many of them were society figures too, they did it in their clubs and tucked away in the corners of the social events of the year.

And because their work was all-comsuming, it dominated every aspect of their lives. Yet at the same time, the volumes of their private correspondence shows that they were diligent landlords–writing frequently to their stewards or consulting with the likes of Coke of Norfolk about drainage or better land management.

Another thing. Although novels and histories are laced together with the juicier bits of Regency gossip with marital infidelities or all-night gambling parties, looking past the headlines, one finds is a pervading emphasis on the happiness of family and home.

The Foreign Secretary, Viscount Castlereagh, for example, was devoted to his wife, even though as everyone notes, she was never his intellectual equal. Yet his letters to her, when they were apart, are tender, endearing and solicitous. When he travelled to the Continent for the Congress of Vienna, she accompanied him, along with her young niece and nephew (and their bulldog, Vernon).

Castlereagh was an early riser, and when in London, used to walk for a couple of hours before heading to the Foreign Office. Then he’d spend the afternoon in the House of Commons and perhaps the evening too. Or, if there wasn’t a debate, he might attend a musical evening because he was devoted to music and loved more than anything to play his cello with friends. His wife, Lady Emily, was the eldest of the Patronesses of Almack’s–the most exclusive social club of the era, a place famous for its weekly assemblies–though he rarely had time to accompany her there.

Sir Spencer Perceval was another one who was devoted to his wife and family; they had twelve children–six boys and six girls.

So, despite the overwork and their many inadequacies, it was men such as these who (over a period of some twenty years) steered Britain to defeat Napoleon. They peacebrokered at the Congress of Vienna, guided Britain through the upheaval brought on by industrialisation and the madness of King George, and supported a navy which put a stop to Napoleon’s colonial ambitions. And throughout it all, they were indomitable in their belief in the goodness and soundness of democracy.

Then, shockingly–because Britain saw itself and not without reason as a peaceful country amidst the maelstrom of Napoleon’s wars–in the midst of all this, the Prime Minister was assassinated.

Hence, on the 12th May 1812, they were no longer just fighting across the Channel, they now had a constitutional crisis on their hands. And the constitution was already in a state as it was–what with the old King mad and blind and the Prince Regent none too popular–or to put it frankly, hated by most and despised by the rest.

Yet, despite all the many odds against them, these men beavered on. They remained resolute, driven by their understanding of duty, honour and loyalty to their King and country.

Their allies were weak-willed, vacillating, often two-faced and venal. The British press in its determination to retain its traditional freedoms often even published secret military plans–which is where Napoleon often learned of British military and naval intentions.

Finally, I was in London the week after the July 7th bombings–there for a conference about Nelson and Trafalgar–and there I began to realise how profoundly unsettling and disconnecting such an event as an assassination is. There is an silent eeriness which cannot be explained, and a knowledge that everything has changed, though one has no idea what that will mean.

And out of all this grew the character of Myddelton–the protagonist of May 1812.

He is in one way an everyman, representing these fine men who gave what they had, contributed what they could to bringing down the greatest tyrant, the rule of the most effective and far-reaching military state the world has ever known. He works himself silly in the service of the government; they, many of them, did.

He is in one way an everyman, representing these fine men who gave what they had, contributed what they could to bringing down the greatest tyrant, the rule of the most effective and far-reaching military state the world has ever known. He works himself silly in the service of the government; they, many of them, did.

Though I trust that unlike Mr. Pitt, he will not work himself to death in the cause.

***

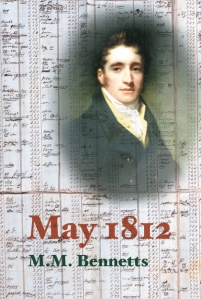

May 1812 is available at www.amazon.co.uk or at www.amazon.com, along with Bennetts’ other works…