This is one of those blog posts I’ve been avoiding writing for some time now. Like for well over a year.

Chiefly because writing it will mean that I might have to get up off my sorry backside and go look in a book or two to confirm a couple of details rather than just opening up my brain and allowing the contents to leak onto the page. Which obviously is my preferred method.

You see, as I’ve observed the popular focus on the early 19th century in novels and because of the undimming interest in Austen, I’ve come to feel that–somehow–there’s this assumption from the few oblique references to it in Austen’s works that the long wars with Revolutionary and Napoleonic France really didn’t impact on the lives of the ordinary and/or aristocratic British at this time.

You see, as I’ve observed the popular focus on the early 19th century in novels and because of the undimming interest in Austen, I’ve come to feel that–somehow–there’s this assumption from the few oblique references to it in Austen’s works that the long wars with Revolutionary and Napoleonic France really didn’t impact on the lives of the ordinary and/or aristocratic British at this time.

But that’s a bit like inferring that Austen and her family didn’t eat eggs. Or wouldn’t have known what they were. She never mentions them, does she? Ergo…

Yet, like eggs or milk or bread, during the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Britain, the ongoing war with France was so much a part of the fabric of daily life that–like her omitting to say that her characters had eggs for breakfast–it possibly didn’t occur to her to mention it. Indeed, this period of war created the very weft and warp of their existence…And the daily reminders of it–they called it the Great War–were so constant, so ubiquitous in their daily lives, that Austen and all her readers took it as understood.

The wars with France between 1793-1815 defined, changed and effected abso-blooming-lutely everything! And they went on and on and on, world without end, amen…

The wars with France between 1793-1815 defined, changed and effected abso-blooming-lutely everything! And they went on and on and on, world without end, amen…

And therefore I would contend that in order to truly understand the period–which some call the Regency (though that’s far from strictly accurate)–one must view it not through a rose-tinted lorgnette with an aristocratic mother-of-pearl handle, but rather through war-tinted spectacles.

Let me show you.

From the outset of the French Revolution, English eyes (and newspapers) had been riveted on the unfolding events in Paris. Remember–France is right across that little arm of water called the Channel (or la Manche if you’re French)…a body of water so narrow, a person can swim it. A small boat can sail it on a fine day…

Until just 250 years previously, at least a part of France had always been owned or ruled by England. The ties, therefore, for all sorts of reasons, were very close. So, it must have seemed like their French cousins and business partners/competition had plunged into a vortex of sanguinary madness such as had never before been seen…

And then, in 1793, four years into this Revolution, the French declared war on Britain. Viscount Castlereagh, when still a young man, was the in the Low Countries during the September Massacres…he daren’t enter France himself…and he read with mounting horror the newspaper accounts of the events that still today are nearly unreadable for their savagery.

And then, in 1793, four years into this Revolution, the French declared war on Britain. Viscount Castlereagh, when still a young man, was the in the Low Countries during the September Massacres…he daren’t enter France himself…and he read with mounting horror the newspaper accounts of the events that still today are nearly unreadable for their savagery.

By 1797, France was strong enough and cocksure enough to attempt invasions of both Ireland (then under British rule) and the British mainland…both, fortunately, fizzled out–Ireland’s due to a blizzard and heaving gale and the mainland’s due to the inferiority of the French troops and the welly of the Welsh they encountered at Fishguard.

But subsequently, all along the south coast, successive governments would embark on building a series of Martello towers to protect against the present threat on invasion.

But subsequently, all along the south coast, successive governments would embark on building a series of Martello towers to protect against the present threat on invasion.

Nor was invasion just a mythical nightmare of a threat. Napoleon, in power since 1799, used the year of the Peace of Amiens (1802-1803) to establish one of the largest army camps at Boulogne–which again, is just across the Channel and which, on a clear day, one can see from the coast of Kent. And what the English saw didn’t make for very reassuring viewing.

For at Boulogne, Napoleon was assembling his troops for invasion. Some 500,000 of them. And often he was there himself, reviewing the troops in full view of the English telescopic lenses trained on the place. Imagine it.

Bearing in mind that ever since the Commonwealth, Britain hadn’t had a standing army per se–or at least nothing on the scale of the European powers–this was pretty scary stuff. If that Corsican upstart managed to get those troops across that tiny slip of water, the result would have been overwhelming. Quite literally.

Thus, the army fellows spent weeks and months working out which were the most likely points of access and then, carving up Kent and Sussex with a series of water courses to hinder the French advance while they, in London, would get the King and royal family away to safety in Wheedon–where they built the early 19th century version of a royal bomb shelter. As the whole of Kent and Sussex were carved up this way, the impact on transportation and even agriculture would have been immense–a daily reminder of the threat across the water.

It seems impossible to fathom, of course, but although he was pretty hot as a general on land, Napoleon never got the hang of water. And that, of course, saved Britain time and again from his invading forces.

Those forces gathering and threatening in Boulogne were only held back as the French waited for a spell of calm in which to cross over. Because Napoleon, judging the difficulty of navigation solely on the width of the Channel, had opted for rafts–large wooden rafts, four feet deep–in which to transport his men, horses, artillery across to England.

And when the first troops were loaded onto these rafts for his inspection, they, er, tipped over. Many soldiers–being unable to swim–drowned, the guns fell into the water and sank, and the horses swam for shore. Whereupon, Napoleon stormed off in one of his classic rages…

The threat may have been lessened for the moment, but the Brits didn’t lose their sense of vulnerability. Not ever.

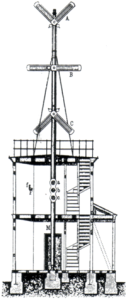

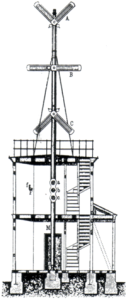

Imagine the disruption to daily life, there, along the south coast. Also along the coast, just as in the weeks preceding the arrival of the Spanish Armada, huge woodpiles were erected to act as beacons should the French be sighted crossing. Added to this, from 1796, there were the telegraph hills or semaphore towers, marring the skyline perhaps, but able to send coded messages inland (Deal to London) in a matter of minutes.

Imagine the disruption to daily life, there, along the south coast. Also along the coast, just as in the weeks preceding the arrival of the Spanish Armada, huge woodpiles were erected to act as beacons should the French be sighted crossing. Added to this, from 1796, there were the telegraph hills or semaphore towers, marring the skyline perhaps, but able to send coded messages inland (Deal to London) in a matter of minutes.

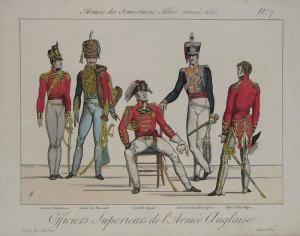

No wonder the militias in those southern counties were particularly active and always recruiting…and all the landed families of each county would have been expected to send their sons and husbands to be officers in the militia, if they hadn’t already bought commissions in the military or gone to sea…

Britain was indubitably on a war footing and that’s how things would remain until 1814…

Everywhere they went, everything they saw and experienced would have emphasised this, if ever they forgot…the newspapers churned out a daily diet of war coverage, and particularly naval coverage, because it was at sea that Britain truly excelled.

Between the years of 1793 and 1812, year upon year, Parliament voted to expand the size of the Royal Navy, taking its size from 135 vessels in 1793 to 584 ships in 1812, with an increase in seamen from 36,000 to 114,000 men. Those seamen all had families, families who missed them whilst they were away, families who grieved if and when they were lost.

In 1792, the size of the merchant marine was already at 118,000, but this too expanded as the Continent was increasingly closed to British trade and British merchants had to seek farther afield for fresh markets.

Admiral Horatio Nelson was the hero of the age–embodying the tenacity, the daring, the sea-savvy of Britons through the centuries, standing up to Continental aggression and aggrandisement alone. He wasn’t just lionised, he was idolised.

Admiral Horatio Nelson was the hero of the age–embodying the tenacity, the daring, the sea-savvy of Britons through the centuries, standing up to Continental aggression and aggrandisement alone. He wasn’t just lionised, he was idolised.

Thousands upon thousands of British boys went to sea because of him–and he was known for treating the younkers well. When he died at Trafalgar, the nation mourned, quite literally. (Have a look at his catafalque in St. Paul’s if you doubt it.)

Again, along the south coast, Portsmouth, Plymouth, Southampton were all swimming with sailors, and with all those industries which support a maritime war–from shipyards to rope-makers to munitions-makers…it was boom-time.

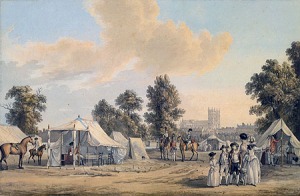

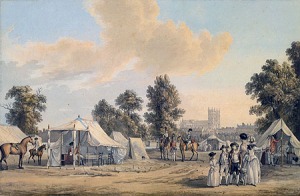

Encampment in St. James’s Park 1780

Hyde Park and numerous other vast public tracts of land were covered with the tents and paraphernalia of military training camps for the army.

But it wasn’t just in the ubiquity of the military that one sees the war–the preferred and very available art form of this period was the cartoon, the satirical print. The war and in particular, Napoleon, provided the fertile imaginations of the cartoonists with a veritable buffet of opportunities for their cynical art and wit.

Given then some 40% of the population was illiterate, it was from these prints, every day displayed in print shop windows, that the British public, gawping and laughing, gathered much of its news and thereby formed its opinions. (That’s every day for nearly 20 years!)

Given then some 40% of the population was illiterate, it was from these prints, every day displayed in print shop windows, that the British public, gawping and laughing, gathered much of its news and thereby formed its opinions. (That’s every day for nearly 20 years!)

The theatres too invariably included a naval spectacle or re-enactment as part of each evening’s bill, in much the same way as during WWII wartime dramas starring John Mills were churned out by Pinewood Studios.

Plays about Nelson were the most popular and the plays of Charles Dibden (then popular, now forgot) reflected this with titles like Naval Pillars, a piece based on Nelson’s victory at Aboukir Bay. Indeed, it was often joked that Dibden should be decorated by the Admiralty for the number of successful naval dramas he’d written…

As if that weren’t enough, the popularity of these maritime spectacles prompted the owners of Sadler’s Wells to create a lake of real water upon their stage as a more lifelike setting for all these pieces. And when one considers that up to 20,000 Londoners attended the theatre each night–and that’s not including Vauxhall Gardens where they also produced martial spectacles or any of the smaller venues where the chief attraction was naval illuminations–that’s when you start to see this war as almost the emotional meat and potatoes of their daily lives.

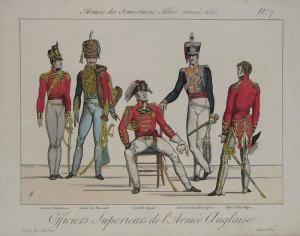

Clothing design, especially for women, embraced the military influence–whether it was riding jackets a la militaire with double rows of buttons and frogging up the bodices and cuffs, or as lady’s head wear, taking its shape from the common shako or the caterpiller-crested helmets of the dragoons, there it is again.

Clothing design, especially for women, embraced the military influence–whether it was riding jackets a la militaire with double rows of buttons and frogging up the bodices and cuffs, or as lady’s head wear, taking its shape from the common shako or the caterpiller-crested helmets of the dragoons, there it is again.

For the underclasses, let’s call them, all along the coast from Cornwall up to East Anglia, the endless French wars led to an increase in smuggling activity upon an industrial scale.

Brandy, French silk, and all sorts were smuggled in, whilst wool for uniforms was smuggled from East Anglia, and just about everything else you can imagine was smuggled from the rest of the coast to European beaches…the organisation and size of these smuggling gangs grew proportionately more sophisticated as the wars raged on, and once Napoleon closed Europe’s borders to British trade, the size of these gangs just mushroomed.

As did the need for an increased presence of Preventive Officers and Revenue Cutters, patrolling the waters of the Solent, the Channel, and the North Sea…

And finally, these wars hit everyone where they’d feel it most, every day. In their pockets.

The war itself, added to the agricultural consequences of years of terrible harvests, led to rampant inflation. Food prices as well as the cost of common goods soared. The lack of grain was so acute that in the years 1808-1812, the Government had been forced to buy thousands of tons of grain from the United States, to be shipped to feed the British troops on the Peninsula.

Not only that, but within five years of its breaking out, the cost of the war had effectively drained the Treasury–the wretched conditions in the Royal Navy had in 1797 led to mutiny and the army was, not to put too fine a point on it, starving. There was, as seen up above, a serious threat of French invasion and Ireland needed troops to ward off any French incursion there.

Not only that, but within five years of its breaking out, the cost of the war had effectively drained the Treasury–the wretched conditions in the Royal Navy had in 1797 led to mutiny and the army was, not to put too fine a point on it, starving. There was, as seen up above, a serious threat of French invasion and Ireland needed troops to ward off any French incursion there.

Pitt the Younger was both Prime Minister as well as Chancellor of the Exchequer (a common combination of offices at that time) and he felt there was a need for an increase in ‘aid and contribution for the prosecution of the war.’ His solution? Income tax. Which was announced in 1798 and became part of every taxpayer’s nightmare from 1799. As today’s Inland Revenue describes it, it was a fairly straightforward proposition:

“Income tax was to be applied in Great Britain (but not Ireland) at a rate of 10% on the total income of the taxpayer from all sources above £60, with reductions on income up to £200. It was to be paid in six equal instalments from June 1799, with an expected return of £10 million in its first year. It actually realised less than £6 million, but the money was vital and a precedent had been set…”

It was, as it turned out, just a drop in the bucket when set against the vast costs of the war. A detailed, country by country, analysis of the subsidies Britain paid to her allies over this twenty year period adds up to the eye-watering sum of £55,228,892.

(If you’d like that in today’s money, that’s £3.5 billion, using the retail price index. Or if you prefer to calculate using average earnings, £55.1 billion.)

And if you think they weren’t constantly grumbling about it…think again.

Nor does that sum include the cost of maintaining a military force in the Peninsula under Wellington, the cost of the disastrous Walcheren expedition, nor the vast (and we’re talking millions) sums secretly paid out to the intelligence agents and spies…The total figure, therefore, is closer to £700 million or £44 billion in today’s dosh.

And none of this even hints at the private sadness and inconsolable losses of those who received, daily, from the Admiralty, from Horse Guards, from commanding officers in Spain, letters informing them that their loved ones would not be returning home…

The war, it was everywhere…it was the carefree laughter and the relief of peace that were missing. And for many had never been known.