Imagine what would have happened if Winston Churchill had been assassinated in May 1944.

Instantly all sorts of frightening scenarios flood the mind, don’t they?

Would Britain have won the war? Was it a Nazi plot? Who or what was the next target? How would security have been expanded? Could it have been expanded? Would Hitler have used the event and the terror it caused to launch an even more appalling strike? An invasion, perhaps? Who would have taken up the job of Prime Minister? Who was left?

The possibilities are endless. And, as I say, frightening.

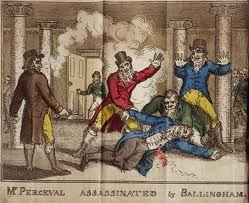

Well, exactly 200 years ago today, this is exactly the situation in which Britain found herself. The assassination of Prime Minister Perceval on 11 May 1812 changed everything!

Well, exactly 200 years ago today, this is exactly the situation in which Britain found herself. The assassination of Prime Minister Perceval on 11 May 1812 changed everything!

Not only that, but Perceval was Chancellor of the Exchequer too. So you might say that the assassin, John Bellingham, had taken out heart of government with a single shot.

And, as in my imagined scenario of 1944, all of Europe was at war and had been for a long, long time.

Times were turbulent, both domestically and abroad. There was hardly a country in Europe whose government or hereditary ruler hadn’t been deposed by Napoleon, mafia-style, and one of his feckless siblings put on the throne. Whole countries had been absorbed by others and turned into French satellites. Across the Atlantic, the Americans had been gearing up for a war in which they could land-grab Canada. At home, there were the Luddite disturbances in the north, the harvests had been bad for several years running, and the King was mad. And they were fighting a war against a military genius with an empire which ranged from Spain to Russia…

Insecurity was normal.

The most immediate effects of the assassination were felt, as was to be expected, here at home. Hence, during the evening of the 11th, the Cabinet met for hours, hammering out a series of security measures which they trusted would keep the peace and prevent panic from overtaking the realm:

Sharpshooters were installed atop government buildings. The Household Guard–those troops responsible for guarding the King and Queen at Windsor and the Prince Regent in London–their numbers were trebled. The mails were stopped until further notice. The militia was called out in mass to patrol the streets of London. The Thames River Police were given orders to search vessels for possible conspirators.

Nevertheless, fear, panic, terror and distress gripped the nation as the news filtered out from the capital. It was no non-event, such as history books might suggest. No, it had more in common with the terrorist attacks of 7/7.

Not only that, but the British were right to suspect the hand of France in it. Because, let’s face it, by 1812, the French Emperor was good at coups.

So, at 5.25 p.m. on 11 May 1812, when Bellingham fired that fatal shot at point-blank range, the MPs tore about the place, shouting it was a conspiracy, and searching for accomplices. There was precedent!

Yet, though it took many people time to accept this, there were no co-conspirators. Indeed, though the British didn’t know it, Napoleon had left Paris for Dresden on the 9th May, on his way to joining his half a million troops massed in Prussia and Poland, ready for the invasion of Russia.

Viscount Castlereagh, the Foreign Secretary, was one of those who doubted that Bellingham’s action had been part of a conspiracy or coup. Even as he assuredly kept his intelligence agents busy looking for enemy agents and the “Black Chamber” of the Post Office was opening every foreign letter…

Which might have been some comfort. But not much.

So what next?

On the 12th, Parliament voted a handsome annuity to Perceval’s wife and 12 children in recognition of his service to the country. Lord Castlereagh tried to speak to the motion, tried to articulate his affection for his friend and colleague, but broke down sobbing and had to be escorted back to his seat.

On the 12th, Parliament voted a handsome annuity to Perceval’s wife and 12 children in recognition of his service to the country. Lord Castlereagh tried to speak to the motion, tried to articulate his affection for his friend and colleague, but broke down sobbing and had to be escorted back to his seat.

London itself appeared to be under martial law–what with the number of militia on every street.

And, there were ramifications. Very serious ones. First off, they needed to find a new Prime Minister. But what would happen to the war effort? Would another Prime Minister continue the fight against Napoleon, would he support Wellington’s efforts in the Peninsula, would he secure the troops Wellington needed, and the supplies?

Meanwhile, what of the assassin, the man who had unleashed this latest bout of insecurity upon the nation?

Since the early hours of the 12th, Bellingham had been incarcerated at Newgate prison, in a cell adjoining the chapel.

All day the 12th and the 13th, as Castlereagh was speaking and weeping, and as Perceval was being laid to rest, Bellingham was visited by the sheriffs and other public functionaries. He remained cheerful and was quite clear in all his conversation that when he came to trial, it would “be seen how far he was justified.” And he repeated that he considered the whole a private matter between himself and the Government which had given him carte blanche to do his worst…

All day the 12th and the 13th, as Castlereagh was speaking and weeping, and as Perceval was being laid to rest, Bellingham was visited by the sheriffs and other public functionaries. He remained cheerful and was quite clear in all his conversation that when he came to trial, it would “be seen how far he was justified.” And he repeated that he considered the whole a private matter between himself and the Government which had given him carte blanche to do his worst…

Four days after the death of the Prime Minister, on the 15th May 1812, Bellingham was brought to trial at the Old Bailey.

At 10.00, the judges took their seats on either side of the Lord Mayor. The recorder, the Duke of Clarence, the Marquis Wellesley and nearly all the aldermen of the City of London crowded onto the bench. The court was packed with MPs, jostling among the throng.

At 10.00, the judges took their seats on either side of the Lord Mayor. The recorder, the Duke of Clarence, the Marquis Wellesley and nearly all the aldermen of the City of London crowded onto the bench. The court was packed with MPs, jostling among the throng.

At length, Bellingham, wearing a light brown surtout coat and a striped yellow waistcoat, appeared–his hair was unpowdered, the press noted. He appeared undismayed by the whole. He bowed to the Court respectfully and even gracefully, some said.

The Attorney General opened the case for the prosecution and several witnesses were called. Several more witnesses were called in defence to testify that they considered Bellingham insane. Eventually, Lord Chief Justice Mansfield gave the summing up, and the jury retired to consider the verdict.

The Attorney General opened the case for the prosecution and several witnesses were called. Several more witnesses were called in defence to testify that they considered Bellingham insane. Eventually, Lord Chief Justice Mansfield gave the summing up, and the jury retired to consider the verdict.

Fourteen minutes later, a guilty verdict was returned. The death sentence was passed and Bellingham was ordered for execution on the following Monday–the 18th.

From the moment of his condemnation, Bellingham (as was custom) was fed on bread and water. Any means of suicide were removed from his cell and he was not allowed to shave–which bothered him. On Sunday, he was visited by a number of religious gentlemen to whom he resolutely maintained his innocence.

But what of the rest of the world? What of the war?

With the sudden vacancy at the top, those men who’d longed for power began shifting about, seeing this as their opportunity. The Opposition party, the Whigs, thought that their moment had arrived and hourly expected messengers to invite them to a meeting with the Prince Regent, during which they would happily accept his offer to form a government–which for the war effort would have been nothing short of disaster.

Meanwhile, Richard Wellesley (brother to the Duke of Wellington) had intended to launch a savage attack on Perceval and his conduct of the war prior to the 11th. But when he’d sat in the House of Lords, with his notes before him, he’d gone blank and hadn’t made the speech. Yet, within a day of Perceval’s death, those notes had been found and their gist printed in The Times.

The nation was appalled by such bad taste and as one turned against Wellesley.

Still, strangely, the Prince Regent did send for him (Wellesley was an old friend and gaming companion), though not to offer him the Premiership. No, it was only to assess how many friends Wellesley could find who would be willing to serve in alongside him in a Cabinet.

That list turned out to be woefully short.

Just one man–George Canning–said yes. (And George Canning was known not to be a gentleman. Indeed, there were just as many men who wouldn’t serve alongside Canning…) Too many were offended by his complaints that Perceval had not been willing to spend enough in support of the war and Lord Wellington’s troops, while at the same time trying to negotiate with Whigs who criticised Perceval for spending too much and who had declared themselves against the was effort in Spain and Portugal.

Next, the Prince Regent would turn to Lord Moira, a Whig, to see if he could form a government…which would have been a very different sort of government and would most assuredly have seen Britain suing for peace with the Americans and with Napoleon–thus ending Wellington’s career. (Would Napoleon have been defeated without him?)

The Whigs were jubilant and loud in their triumph. The officers and under-secretaries at the Admiralty and at Horse Guards were appalled.

But again, Moira turned to George Canning and his followers for support, so this went nowhere. Even as the country seethed with instability and uncertainty.

Eventually, another of William Pitt’s disciples (as Castlereagh and Perceval were), Lord Liverpool, was appointed Prime Minister by the Prince Regent. He kept much of the existing Cabinet appointments intact–Castlereagh remained at the Foreign Office, but added Leader of the House to his list of duties. And the war against the French was pursued even more vigorously to the total defeat of the French Empire and the abdication of Napoleon Bonaparte.

But, 200 years ago today, they didn’t know all that…and on 15th May, they couldn’t even begin to imagine it.

at five o’clock in the afternoon, Sir Spencer Perceval, the Prime Minister, was shot in the lobby of the House of Commons. He died almost instantly.

at five o’clock in the afternoon, Sir Spencer Perceval, the Prime Minister, was shot in the lobby of the House of Commons. He died almost instantly.