Funnily enough, I was just reading a blog by multi-novel historical fiction author, Allan Massie, about strong opinions and how too often they’re based on knowing or understanding less than we might before we blast our mouths off.

Ehem.

So anyway…recently I’ve been dipping into the research on the build-up to the War of 1812 again–reading the speeches given by those early presidential icons, Jefferson and Madison, for example, reading histories of the period written both by American and British historians, as well as various eye-witness accounts, plus the American press coverage of events and comparing those to the British reports…

…and spending quality time with the percentages of British sailors employed aboard American merchant ships at the time…and analysing other data, such as tax receipts…

(I know, I know…the wild and crazy world of an historian! Where do I get the energy?)

And in the midst of all this, I have been forced to conclude that I have got something (many things) completely and utterly wrong.

And when I say wrong, I mean wrong.

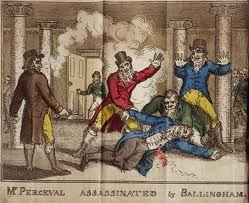

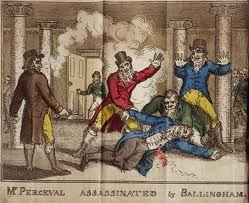

You see, I had always, always, always believed and been wholly convinced in my mind that had the Americans in Congress known at the time of Prime Minister Perceval’s assassination on 11 May 1812 (which of course they didn’t due to the length of time it took for news to travel), they would never, ever, ever have launched into war so precipitately in June.

You see, I had always, always, always believed and been wholly convinced in my mind that had the Americans in Congress known at the time of Prime Minister Perceval’s assassination on 11 May 1812 (which of course they didn’t due to the length of time it took for news to travel), they would never, ever, ever have launched into war so precipitately in June.

They would have respected our loss, respected the gravity of the situation, appreciated that we were in the midst of an existential struggle against the most powerful military dictator the world had ever known, and stepped back from the brink, or at least out of deference to the grieving nation, postponed their decision…and maybe sent flowers to the grieving widow.

Or something.

Well, I’m here to say today, I got that wrong.

And not just a little nibbling about the edges wrong. We’re talking very wrong.

Because you see, I–like probably most people–had completely and utterly swallowed all the Anglo-American political PR that grew up during the 20th century, during two world wars, in which we were the firmest of friends, the most devoted of allies, that we had a special relationship…

Yet I have to tell you–what I have found is precisely the opposite. And it has shocked the socks off me.

There were a great many reasons why I got it so wrong.

One, of course, was that I failed to realise the depth of Jefferson’s hatred of the British. And the same goes for Madison.

I failed to comprehend Jefferson’s absolute conviction that British commerce was corrupting the morals of the New England merchants and that he saw the moral purpose of the US to be in building an agrarian republican superstate, wholly independent of the sordid aspects of commerce and trade, ruled by those who agreed with him. (No, I am not making this up. If only…)

Equally, initially, I failed to read far back enough, and to note that the War Hawks in the Republican party had been making a vehement case for war against the British at least as early as autumn session of Congress which commenced in November 1811.

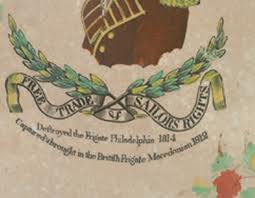

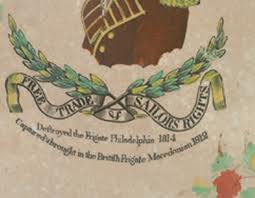

I also failed to understand just what a nonsense the whole “Free Trade and Sailor’s Rights” slogan was.

I also failed to understand just what a nonsense the whole “Free Trade and Sailor’s Rights” slogan was.

I thought–in my quaint little Japanese fashion, said Yum Yum–that the concept of stopping ships for deserters was some nasty-wasty thing the Brits had devised to annoy the Americans and that the Yankees were rightfully protesting.

Ehem.

And those stats I was telling you about? Yes, well, it transpires, according to those stats, that some 50% of the seafaring workforce on American ships in the early years of the 19th century were in fact British. And the American shippers were fully aware that they couldn’t function properly without British manpower.

Moreover, the law allowing the vessels of the Royal Navy to stop foreign ships in time of war and search for British sailors who by rights (I’m sure we’d all agree, if we think of it in terms of WW2, say) should be serving their country…that law dates back to the Seven Years’ War in the 1750’s.

Moreover, the law allowing the vessels of the Royal Navy to stop foreign ships in time of war and search for British sailors who by rights (I’m sure we’d all agree, if we think of it in terms of WW2, say) should be serving their country…that law dates back to the Seven Years’ War in the 1750’s.

It wasn’t something the British government hastily cooked up to vex their colonial cousins.

Furthermore, the American shippers and captains knew very well that Britain was at war with the French Empire and that it was a near run thing. They may have lived on the other side of the world, but they weren’t stupid.

There’s another tricksy bit to this and that’s the matter of nationality. Until the fledgling US introduced the idea, nationality and citizenship rested entirely on where one was born. Full stop. It was a non-topic. If you were born in France, you were French. If you were born in Britain, you were British.

However, the Americans introduced the idea of taking citizenship and made it possible for those coming from other parts of the world to take up American citizenship. Fine, okay…

But this, unsurprisingly, gave rise to a nifty little scam in forged documents, which were cheap and easy to come by for sailors who’d prefer to work for better wages on American merchant ships, rather than be subject to the discipline, etc. of life in the Royal Navy. And come by them they did. In droves.

So, when the Royal Navy stopped and searched ships looking for deserters (it was a time of war, no doubt about that), and these (often known to the Navy by name and description) tars then protested that they were Americans and here were the dodgy papers to prove it…well, I think you can see, it wasn’t really something one would go to war over. Was it? And everybody knew it.

Also, the number of genuine Americans (if I may designate them as such), taken from American ships in this way–well numbers indicate that not more than 10% of those taken were actually the people they said they were…

What I also failed to realise was just how chummy the American statesmen were with France and Napoleon.

What I also failed to realise was just how chummy the American statesmen were with France and Napoleon.

I kept assuming–wrongly as I now know–that they were being naive, that Bonaparte was hoodwinking them as he had everyone else. That they didn’t realise that Bonaparte would say one thing and do another and that he didn’t give a bean about anyone but himself. Yup, got that wrong too.

Jefferson was a confirmed Francophile. But so was Joel Barlow, who was sent as Ambassador to Paris in 1811.

And the fellow that the French sent over to be Ambassador in Washington, D.C., Serurier, well he was as honey-tongued a manipulator as ever there was and he smooth-talked anyone who would listen–a carefully regulated steady dripfeed of anti-British venom, plus suppression or denial of what the French were really up to, all wrapped up in a cherry-flavoured sugar coating of French endearments and protestations of eternal love and admiration.

Bonaparte pulled the strings and they all danced.

From 1808, he was telling the Americans that they must ‘defend their flag’ as he urged them to make war on the British.

He and his minions were constantly ragging the Americans–Jefferson, Monroe and Madison–to take on the British for their many anti-free market activities, whilst at the very same time he was ordering American ships and their cargoes seized, held, and confiscated, even as Barlow pressed for indemnity payments and Napoleon’s ministers hemmed and hawed.

And every time Barlow was convinced he was reaching some sort of agreement for compensation payments and hammering out a trade agreement that would open up the European market to American trade, the French apparatchiks would dither, and Bonaparte would order stricter adherence to the Continental System particularly as regards the Americans.

And every time Barlow was convinced he was reaching some sort of agreement for compensation payments and hammering out a trade agreement that would open up the European market to American trade, the French apparatchiks would dither, and Bonaparte would order stricter adherence to the Continental System particularly as regards the Americans.

Even the emollient language of American historian, P.P. Hill, cannot disguise the fact that the American policy was to turn a blind eye, no matter how egregious the French behaviour. Even when in February 1812, French privateers burnt at sea the American ships laden with wheat and bound for Spain to feed Wellington’s troops there…

Here’s the recap written by Captain Philip Broke, who got his info from the American newspapers at the time: “The war party are certainly a wicked and perverse set of men and acting in downright enmity to the welfare of all free nations as well as their natural allies–the mass of the party are sordid, grovelling men who would involve their country in a war for a shilling percent more profit on their particular trade and are perfectly indifferent whether they league themselves with honor or oppression–provided they get their mammon. Some of their leaders wish for a war only to get places and commands…”

John Randolph wrote: “Agrarian cupidity, not maritime right, urges the war…a war of rapine, privateering, a scuffle and scramble for plunder.”

And even in April 1812, when the French produced what the Americans knew was a fraud–the so-called St Cloud Decree–in which Napoleon claimed to have ended the trade embargoes against America a year earlier. (He cunningly had it backdated, by hand…but one gathers the ink was barely dry on the page…)

Even then, when they knew they were being had, when Napoleon’s contempt for American compensation claims and their anger against extortionate French tariffs were at an all-time high, even then, they did not turn from their course. Indeed, the Republican politicians suppressed all talk of the fraud and various other French cons.

Because, you see, the outcome had already been decided. The Americans knew that Bonaparte planned to invade Russia; they expected him to triumph there, and then, they anticipated that he would turn the full might of his military Empire upon Britain.

Because, you see, the outcome had already been decided. The Americans knew that Bonaparte planned to invade Russia; they expected him to triumph there, and then, they anticipated that he would turn the full might of his military Empire upon Britain.

And they wanted to be on the winning side, the side that would give them Canada, no questions asked, the side that would overlook their land-grab in Spanish Florida…And that side, they believed, was with Napoleon and his Empire.

Added to which, they firmly believed that with the troops tied up in Spain, Britain would lack the troops to send to defend the Canadian border, and they meant to enjoy that freedom by strolling up there and taking the place over. (Just like they’d done in the Spanish territories of Florida…)

The British government, for their part, couldn’t believe it when Congress declared war. They were convinced–despite the tide of vitriolic abuse which had been pouring out of American newspapers for the past two-three years–that the American people did not want war, they wanted fair trade.

They also believed–knowing as they did just how costly a war actually was–that no one in their right mind would go to war over a principle such as “Free trade and Sailors’ Rights”.

So…I got it wrong. The American Congress of 1812 wouldn’t have halted their determined march to war had they learned of Prime Minister Perceval’s death. Indeed, it saddens me greatly to say, I think they may have held a party…

1) What is the name of your character? Is he/she fictional or a historic person? As in my previous novel, Of Honest Fame, there are a plethora of central characters, both historic and fictional. But the one I’ve chosen to talk about today is Sir George Shuster, otherwise known as Captain Shuster or Georgie.

1) What is the name of your character? Is he/she fictional or a historic person? As in my previous novel, Of Honest Fame, there are a plethora of central characters, both historic and fictional. But the one I’ve chosen to talk about today is Sir George Shuster, otherwise known as Captain Shuster or Georgie. Then he took up his post again in Of Honest Fame, investigating a series of leaks, escaped POW’s and murders connected with the British Foreign Office. But he was home in Great Britain where there were clean shirts and clean water and no one shooting at him, and after all the trauma of war he’d experienced, he was more than eager to put down re-establish himself there, to settle back in and leave the past and its nightmares behind.

Then he took up his post again in Of Honest Fame, investigating a series of leaks, escaped POW’s and murders connected with the British Foreign Office. But he was home in Great Britain where there were clean shirts and clean water and no one shooting at him, and after all the trauma of war he’d experienced, he was more than eager to put down re-establish himself there, to settle back in and leave the past and its nightmares behind. As for reading about it, well, much of my research for this next book has had to be from Russian and Prussian sources, which might make reading about a little tricky…that’s why you have me, isn’t it? But as things unfold, I shall keep everyone alerted to my…er…trials, tribulations, (expletives) and transmogrifications…

As for reading about it, well, much of my research for this next book has had to be from Russian and Prussian sources, which might make reading about a little tricky…that’s why you have me, isn’t it? But as things unfold, I shall keep everyone alerted to my…er…trials, tribulations, (expletives) and transmogrifications…