Where shall I start?

Possibly with a definition of total war, yes?

Total war, which is what WWII most definitely was, is warfare that does not distinguish between civilians and combatants, but rather holds that whoever is not fighting alongside one is an enemy and therefore should be exterminated. Hence just as Hitler was clear that he had to wipe out all resistance to his plans of conquest and rule wherever it might be found, so too 200 years ago, the French brought that level of savage conquest to every corner of Europe…

So, let’s go back to the beginning, shall we?

What happened in 1789 that changed the course of world history? Yes, that’s right, Jane Austen had her fourteenth birthday–though what kind of cakey she had or if she had cakey, I can’t tell you.

However, there was something else, which involved a few more people and was possibly–I know it’s hard to credit–even more important than that. It was the beginning of the French Revolution.

Now before I go any further, let me just say that the coming of the French Revolution was no surprise to observers of the age. France had been bankrupt for some time, the political machine addicted to privilege, the various classes entrenched in their opposition to change, the general population impoverished, the crime rate staggering, the roads impassable, the harvests meagre, inflation was soaring and the king and queen, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, alienated from everyone.

Now before I go any further, let me just say that the coming of the French Revolution was no surprise to observers of the age. France had been bankrupt for some time, the political machine addicted to privilege, the various classes entrenched in their opposition to change, the general population impoverished, the crime rate staggering, the roads impassable, the harvests meagre, inflation was soaring and the king and queen, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, alienated from everyone.

The question hadn’t been if there would be a seismic change, the questions were when and how and what? But no one in their wildest nightmares imagined what was to come.

Within a few months, the summer stand-off between king and people and various political factions had devolved into an elitest power struggle, the Third Estate (everyone besides the aristocracy and clergy) were in the ascendancy, and the country was fast sliding past civil disobedience into fierce sectarian violence. By the summer of 1791, King Louis XVI was a prisoner and counter-revolution was sweeping the countryside, in its wake bloody suppression in which thousands were killed.

In Paris, the revolutionaries were relentless and mesmerising in their determination to take their ideology of republican fervour and a moral cleansing (as they saw it) of bloodshed to all the crowned heads in Europe. On 20th April 1792, France declared war on Austria.

Prussia joined Austria on the battlefield against this new Republican France–and the pitiless wars that would consume the Continent began as France rolled out her vast conscript armies, which over the next 23 years would unleash a torrent of ruthless destruction, pillage, economic strangulation and savage invasion, reaching from the Atlantic shores of Portugal in the west to Egypt and the Acre in the south, and the heart of Russia in the east.

It was to become the first total war, invented by the French, by Robespierre and St Just and other French ideologues. (Another word for that might be sociopaths…)

In Paris, where paranoia and mob-rule dominated, some 4000-6000 people fell victim over just four days to the vicious slaughter of the September Massacres.

The rest of Europe looked on in stunned and speechless horror.

Louis XVI was eventually tried and found guilty of treason. He was executed by guillotine on 21st January 1793. By late that spring, the vainglorious and perhaps pot-valiant rulers of France had declared war on virtually every country in Europe–however woefully unprepared for such a situation they were.

Louis XVI was eventually tried and found guilty of treason. He was executed by guillotine on 21st January 1793. By late that spring, the vainglorious and perhaps pot-valiant rulers of France had declared war on virtually every country in Europe–however woefully unprepared for such a situation they were.

However, failing to succeed with fervour and without much else on the battlefield, with France itself in a state of roiling revolution, counter-revolution and economic disaster, the ‘war party’ of the Brissotins fell, leaving the Committee of Public Safety–a 12 man governing body which included the lawyer, Maximilien Robespierre, Louis de St. Just, and later the painter Jacques-Louis David–in charge of what would soon be known as the Reign of Terror.

Louis XVI’s wife, the hated Austrian princess Marie Antoinette, was beheaded on 16 October 1793.

But she and Louis were hardly alone. Over the next two years, nearly 40,000 men, women and children would be executed in Paris and throughout France, their deaths ordered by this group of men who believed in the ‘complete destruction of everything that is opposed to the committee.’

Nor were they all or even mostly aristocrats who climbed the scaffold to the guillotine. Only 17% of the victims of this genocide were of aristocratic birth. The others were predominantly made up of the clergy–prayer had been outlawed as anti-revolutionary and subversive and the clergy turned out into the streets–and members of the Third Estate…

But these most fanatical leaders of the Revolution soon themselves fell foul of public mood which had begun to swing away from their devastating devotion to bloodshed. On 28 July 1794, Robespierre himself, along with others of the committee, was guillotined.

But these most fanatical leaders of the Revolution soon themselves fell foul of public mood which had begun to swing away from their devastating devotion to bloodshed. On 28 July 1794, Robespierre himself, along with others of the committee, was guillotined.

Meanwhile, a young Corsican artillery officer had been dispatched to serve in the siege by the British of Toulon in September 1793. He was energetic, determined, and even wildly fearless in the face of overwhelming odds.

His name was Napoleon Buonaparte, and for his part in the successful action in Toulon, he was made a brigadier, and France, longing for a victory after so many losses against the better equipped, better-fed, better-led armies ranged against her, rejoiced.

1794 saw the French armies getting walloped on all fronts. 1795 saw a new executive government for France, this time a Directory. But not everyone was thrilled with the turn of events and on 3 October, Paris erupted (yet again) in a revolt which was soon put down by the Directory’s defenders near the Tuileries palace.

Among these defenders was Bonaparte, and whatever the true case of the situation, within days the conviction had spread that it was Napoleon Bonaparte who had stilled the insurrection with “a whiff of grapeshot”. He was the hero of the hour, the darling of the Parisian salons.

Among these defenders was Bonaparte, and whatever the true case of the situation, within days the conviction had spread that it was Napoleon Bonaparte who had stilled the insurrection with “a whiff of grapeshot”. He was the hero of the hour, the darling of the Parisian salons.

On 9 March 1796, he married Rose de Beauharnais, whom he renamed Josephine.

Two days later, he departed for Italy to command the French so-called Army of Italy. And it is really from this point forward that the fate of France, indeed the fate of Europe, merges with the personal fortunes of this opportunist, energetic, glory-seeking Corsican general.

His 1796 conquest of Italy left Europe agog. Within a few brief months, the independent principalities of Piedmont, Tuscany, Modena and the Papal States had been forced to make peace with him. His rag-tag army had overrun northern Italy and had defeated a series of Austrian armies.

Whilst Buonaparte was away from Paris, France sought to spearhead an invasion of Britain, starting with an invasion force of 40,000 men who were to land in Ireland, cause a Republican uprising, and then move on to overthrow the British government. But fierce weather drove the French troop ships from the coast of Ireland–and the plan was abandoned.

Elsewhere in Europe, French defeats served only to highlight his brilliance on the battlefield, reinforcing his importance to the Directory. And the Directory needed good news, for France itself had sunk into a vacuum of political corruption, economic privation and failure, indolence and lawlessness–even as in Italy, Napoleon had transformed the army into a propaganda machine and a power base and was trying his hand at state-making, turfing out the former rulers and creating the Cispadane and Transpadane Republics (which he would subsequently transform into the Cisalpine and Ligurian Republics).

Verona surrendered; Venice was seized. By the end of the summer, Napoleon had made himself virtual king of northern Italy, and the French plunder of that land was on a scale unsurpassed either before or since, with Napoleon the chief beneficiary.

By December 1797, when he returned to Paris, Napoleon was the national hero. And this made him dangerous. Very dangerous indeed. Hence, when he put forward his new bright idea to the Directory–still a cesspool of corruption and connivance–that he should take an army to Egypt, conquer it and set up a French colony there which could in turn threaten Great Britain’s trade with India, the Directory said, “What a great idea! Off you go then…”

But that didn’t turn out so well, for in the middle of his spate of victories over the ill-prepared, mediaevally-armed Mamelukes, Britain’s Lord Nelson led the Royal Navy to defeat and destroy the French fleet at Aboukir Bay on 1st-2nd August 1798, thus marooning the French army.

But that didn’t turn out so well, for in the middle of his spate of victories over the ill-prepared, mediaevally-armed Mamelukes, Britain’s Lord Nelson led the Royal Navy to defeat and destroy the French fleet at Aboukir Bay on 1st-2nd August 1798, thus marooning the French army.

Eventually, his army crippled by disease and casualties sustained at the Battle of Acre, Napoleon abandoned them, fleeing back to France on 24th August 1799, where he proclaimed the whole to have been a rip-roaring success and victory for France. (No kidding.) But having got a taste for command and absolute power, his ambitions could not be contained.

With the help of his brother, Lucien, he orchestrated a coup d’etat against the financially incompetent Directory on 9th November, aka 17 Brumaire under the arcane Revolutionary calendar.

Within weeks, a new government, a Consulate of three with Napoleon as First Consul was established. On 17th February 1800, he took possession of the Tuileries Palace. He was, by right of the new Constitution, the supreme ruler of France.

What follows for the next fourteen years is an unending history of misery, of conquest, battle, pillage and destruction, as Napoleon and his armies swept aside all barriers that stood in the way of his absolute soon-to-be imperial power and greed. During this period of the wars, Britain, ruling the waves, would diplomatically construct coalition after coalition of European powers to oppose the Napoleonic military machine–paying out millions in subsidies to Prussia, Russia, Austria, Portugal and Spain. Yet for a decade, no one but the British–and that at sea–could defeat the seemingly indefatigable French.

And curiously, for the first couple of years of his reign the battlefields were quiet-ish, as Napoleon consolidated his power at home, reconstituting the judiciary, the ministries, the civil code, the education system, the law-book–all to suit himself.

Britain was feeling the pinch too and between 1802-1803, under the terms of a thing called the Peace of Amiens, Europe was at peace.

Britain was feeling the pinch too and between 1802-1803, under the terms of a thing called the Peace of Amiens, Europe was at peace.

Sort of.

I say sort of, because Napoleon was merely using the time to refashion the state in his own image, to build and train a conscript army, the size and force of which had never been seen before. And of course, to arrange for his self-crowning as Emperor.

Britain then remained Napoleonic France’s implacable foe. Consequently, Napoleon began to amass troops for an invasion, situating this ginormous military camp at Boulogne (on a clear day, it could be seen from across the English Channel). The Royal Navy kept up a constant patrol, bless them.

France, now allied with Spain, sent forth a fleet to draw them away from the Channel, thus to provide a 24-hour window, during which time, the thousands of troops might be transported across the Channel to being the invasion.

There were two catches to this great plan. One, the “transportation” consisted of four-foot deep barges, which, in the choppy waters of the Channel capsized almost immediately weight was put on them–the horses swam back to shore, the non-swimming troops weren’t so fortunate.

And two, that pesky Lord Nelson again, who led the fleet to victory over the French and Spanish combined fleets on 21st October 1805 at Trafalgar. France would never again challenge Britain at sea and subsequently, Napoleon’s insatiable lust for conquest would be confined to Continental Europe.

And two, that pesky Lord Nelson again, who led the fleet to victory over the French and Spanish combined fleets on 21st October 1805 at Trafalgar. France would never again challenge Britain at sea and subsequently, Napoleon’s insatiable lust for conquest would be confined to Continental Europe.

In response, he marched his army at breakneck pace across Europe, roughing up the German principalities through which he travelled, and smashing the allied Austro-Russian armies at the Battle of Austerlitz on 2 December (combined casualties–upwards of 30,000 men).

As a result, the centuries-old Austrian Empire was dramatically reduced and Napoleon set up the Confederation of the Rhine at Austria’s expense in the early months of 1806.

Less than a year later, on 14th October 1806, Napoleon led his troops to victory over the Prussians and Saxons at Jena; at Auerstedt on the same day, another defeat for the Allies, this time the Prussians alone, with over 10,000 Prussian casualties.

The subsequent days became a roll-call of Battles and Allied losses, of French sieges and Allied capitulations, which only concluded at the Battle of Friedland on 14th June 1807 with a costly victory over the Russians.

And all the while, these massive armies were in the field, displacing whole villages, eating everything in sight, pillaging, ripping up fruit trees to feed their cooking fires, creating a veritable sea of refugees who sought safety in the nearest forests where they fell prey to the thousands and thousands of deserters and bandits…

The Treaty of Tilsit agreed between Tsar Alexander and Napoleon, on 25th June, temporarily put an end to hostilities, leaving Napoleon free to carve up Europe as he chose. And he did.

The Treaty of Tilsit agreed between Tsar Alexander and Napoleon, on 25th June, temporarily put an end to hostilities, leaving Napoleon free to carve up Europe as he chose. And he did.

But soon, again, he grew restless, and now greedy for the apparently rich prize of Spain, in September 1807, he sent an army corps to the Spanish border, where they were to demand that Spain allow them to cross their territory in order to subdue Portugal who were allied with Britain.

By the end of November, the Portuguese royal family were being bundled aboard British ships, to seek sanctuary in South America. Displeased and still greedy, Napoleon launched a full-scale invasion of Spain itself, otherwise known as his first really big mistake. Certainly it precipitated the most brutal and savage phase of France’s conquest over her European neighbours.

Britain eventually sent a small force to aid the Spaniards who were rebelling against the French invaders, first under the command of Sir John Moore and upon his death, under the command of Sir Arthur Wellesley. Wellesley’s subsequent series of small but significant victories over the French were a first sign that France might be defeated in the field.

Britain eventually sent a small force to aid the Spaniards who were rebelling against the French invaders, first under the command of Sir John Moore and upon his death, under the command of Sir Arthur Wellesley. Wellesley’s subsequent series of small but significant victories over the French were a first sign that France might be defeated in the field.

Napoleon now opted for economic warfare against Britain by launching the Continental System which was designed to deprive Britain of her worldwide export market by closing all European ports to her shipping and goods. Unfortunately, he couldn’t control the seas–he had no navy–so Britain continued to trade and continued to subsidise European resistance to French rule. European businesses and ports, however, went bankrupt in their thousands, and privation and shortages of every kind of commodity became commonplace. (Smuggling boomed though…)

By January 1811, Napoleon (having turned his back on the ‘Spanish Ulcer’) had decided to invade Russia. For the next year, he concentrated troops in Prussia (now a vassal state to France) until he had a combined Grande Armee of at least 480,000 men. By the end of June, having ravished Poland, they were crossing the Niemen into Russian territory.

On 7th September they defeated-ish the Russian army at the Battle of Borodino–which was the most costly battle in terms of human life ever fought at that time. Though they took Moscow, the French were soon forced to retreat amidst terrible winter conditions which destroyed the remnants of this once great army.

On 7th September they defeated-ish the Russian army at the Battle of Borodino–which was the most costly battle in terms of human life ever fought at that time. Though they took Moscow, the French were soon forced to retreat amidst terrible winter conditions which destroyed the remnants of this once great army.

On 4th December, Napoleon abandoned his troops as he had once before. He reached Paris on 19th December. (Only some 30,000 of his men were all that was left to struggle home in his wake.)

(Equally, while he had been otherwise occupied on the Eastern front, Wellesley–now Lord Wellington–had been busily driving the French out of Spain…)

Within a day, he had summoned his ministers, calling for a new levy of conscripts…and he was ready to take to the field again by April. By April too, Prussia and Russia were once again allied against him with Britain as paymaster. His defeat of the Allies, first at Lutzen and then at Bautzen (Germany), caused some to fear. But Austria negotiated a truce for the summer months, during which time, Russia and Prussia called up further troops and organised their supply lines.

Austria tried to press Napoleon for peace, but he–as ever the Corsican strongman–refused to negotiate and blew them off.

The Allied powers of Russia, Prussia and Austria took the field against Napoleon’s new Grande Armee and inflicted staggering casualties upon the French forces at the three-day Battle of Leipzig, 16th-18th October 1813.

The Allied powers of Russia, Prussia and Austria took the field against Napoleon’s new Grande Armee and inflicted staggering casualties upon the French forces at the three-day Battle of Leipzig, 16th-18th October 1813.

The disorganised French fled westward, and for the next several months, Napoleon attempted to stave off the advancing Allied invasion of France, but with his supplies, his finances, and his wasted troops exhausted, he ultimately failed.

Thus after the Battle of Paris on 30th March 1814, Tsar Alexander entered the city in triumph. On 6th April, Napoleon was forced by his generals to abdicate power.

From the southwest, Wellington was invading France as well.

Let joy reign supreme… Napoleon–at the behest of Tsar Alexander–was dispatched to the island of Elba. Which he didn’t much care for.

A Congress was convened in Vienna in September of that year, with the brief to rebalance and redistribute power to the various countries. They were dancing and discussing and negotiating the final settlements when it was announced that Napoleon had escaped from his island prison and was making his way through France, raising a new army…

The Allies, now led by the Duke of Wellington, met Napoleon’s army on 16th-18th June 1815, at a series of battles which we refer to as Waterloo. Napoleon was defeated. At a cost of at least 95,000 casualties, drawn from all corners of Europe.

This time, there were to be no mistakes. Napoleon was sent, aboard a British ship, to the island of St. Helena…where he would die in 1821. Possibly of stomach cancer. Possibly he was poisoned…

The Allies resumed their negotiations in Paris and Vienna, though this time they were in no mood to conciliate French demands for anything. The treasures Napoleon and his troops had looted from the farthest ends of Europe were removed from the Louvre and sent home. France was restored to its pre-Revolutionary borders. Italian and German nationalism had been ignited which would eventually lead to the uprisings of the 1840s and 50s.

Over the course of the wars, Britain had paid out between £55 and £65 million in subsidies to her Continental Allies. (That’s somewhere between £3.5 billion and £4.6 billion in today’s money.)

More than six million people had lost their lives, hundreds of thousands more were displaced refugees, and it would take until 1890 for the populations of Europe to regain their pre-Revolutionary numbers.

The number of those who lost their lives stands at somewhere between five and six million…but that’s probably not counting those who died as a result of starvation due to the French armies eating up every speck of food in a country including next year’s grain so there would be no harvest, those who lost their lives fleeing the violence, or those who were infected with any of the many diseases the French army spread (like syphilis) which killed its victims within five or so years of contraction.

Likewise we have only the vaguest idea of how many Russian civilians died courtesy of the French invasion in 1812 and its ghastly aftermath.

And thus, until 1917 or thereabouts, the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars were known simply as the Great War.

Alle Seelen ruhn in Frieden.

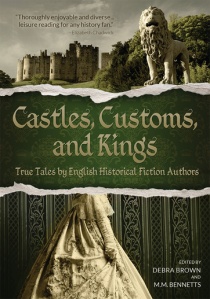

It hits the shelves on the 23rd September 2013, this tome does, courtesy of Madison Street Publishing.

It hits the shelves on the 23rd September 2013, this tome does, courtesy of Madison Street Publishing. “This book is a scholarly treasure trove with a wide appeal. It covers everything from the first English word to the food (and recipes) served at a Tudor feast. If you are interested in nonfiction works on England, history, and/or royalty you will find a book that you will return to. Fans of historical fiction and England will find the book rich in supplemental information to complement their reading with an introduction to authors of works they might enjoy.”

“This book is a scholarly treasure trove with a wide appeal. It covers everything from the first English word to the food (and recipes) served at a Tudor feast. If you are interested in nonfiction works on England, history, and/or royalty you will find a book that you will return to. Fans of historical fiction and England will find the book rich in supplemental information to complement their reading with an introduction to authors of works they might enjoy.”