Sorry, sorry, sorry…yes, that headline is me laughing at my own jokes. Sorry. It was too good to pass up.

Anyway…codes. Secret codes.

Well…The reason I’m on about this at the minute is that last Sunday, as announced in this news feature, a page of a letter written by Napoleon in code was going under the hammer at some auction or other. And this particular letter was of great interest because it detailed what the French army were to do–blow stuff up–upon their retreat from Moscow in October 1812. So, of great interest to historians and particularly Russian historians.

Well…The reason I’m on about this at the minute is that last Sunday, as announced in this news feature, a page of a letter written by Napoleon in code was going under the hammer at some auction or other. And this particular letter was of great interest because it detailed what the French army were to do–blow stuff up–upon their retreat from Moscow in October 1812. So, of great interest to historians and particularly Russian historians.

But of course, as so often happens, the, er, author of this bijou article-ette didn’t quite get his facts right with his comments about Napoleon’s Secret Coded Letter…chiefly because, he writes as though this was the only one. A one-off. And how spooky, secret-agenty was that?

Er, not exactly.

Since the days of Louis XIV, back in the late 17th century, the French Foreign Ministry had excelled in code-work. And let’s face it, in those days of shifting loyalties and French expansionism, they probably needed to.

Anyway, over the hundred or so years, they had developed several examples of petits chiffres (little ciphers) of some 600 characters.

And the way this thing worked was they had the numbers 1-600 written down on their deciphering sheet, and corresponding to these numbers were words, so that when the secretary wrote down his message, he would substitute the numbers for the words in the sentences, which resulted in a pretty confusing or inconclusive reading of the information for anyone without the code book.

By 1750 or so, this enciphering table had been expanded to 1200 numbers, rendering the encrypted messages even more difficult to interpret. And of course, there were more esoteric codes employing hieroglyphs too.

Copies of these ciphering tables had remained untouched during the years of Revolution in the French foreign ministry drawers, just waiting to be rediscovered and re-used and expanded upon. But at first Napoleon didn’t have need of them.

In the early Napoleonic campaigns, they had used letters written in a petit chiffre–which were normally composed of number substitutions for about 50 words, but these were quite easy to crack–and if that message fell into the wrong hands, it would only be a matter of a few hours before the contents were decoded.

However, when Napoleonic troops invaded Spain and Portugal in 1808, they found themselves in exceedingly hostile territory, among exceedingly hostile natives…and with the two main armies being separated by hundreds of miles across exceedingly hostile terrain where anything might happen…well…to put it mildly, communication just got a whole lot more difficult.

Yes, in France and across much of the conquered German lands to the east, telegraphs had been erected to aid in the speedy transmission of information from Paris to the other parts of the Napoleonic Empire, but this wasn’t going to work in Spain. The Pyrenees Mountains were in the way, for a start…

So, it’s at this point, that they go back to the idea of enciphering their letters. That way, if the Spanish guerrillas captured the courier (as so often happened) even if that happened, neither he, nor, after 1809, his British counterparts and allies could read the thing. Brilliant, yes? And by 1811, the need was acute.

And it’s at this point that Marshal Marmont, assuming command of the Army of Portugal as they called these French divisions, ordered the creation of a new cipher–bigger than the old–comprised of some 1200 numeric substitutions. And a great many of those numerals would have been used to indicate locations. Genius!

And it’s at this point that Marshal Marmont, assuming command of the Army of Portugal as they called these French divisions, ordered the creation of a new cipher–bigger than the old–comprised of some 1200 numeric substitutions. And a great many of those numerals would have been used to indicate locations. Genius!

The next step came from Napoleon himself who ordered the creation of a new cipher, a grand chiffre, for his brother Joseph, nominally King of Spain, (he’s a bit of a feckless loser, to be honest) and to be used to shore up Joseph’s waning authority–and he starts sending the letters to Spain written in this. But the problem was that not everyone, including Joseph, had the new encryption tables…So, the King resorts to writing things out–writing en clair, as it’s known.

The British too, at this point, are coming into possession of more and more of these coded letters and they’ve got their own code-breakers beavering away at cracking the codes.

The codes vary in difficulty.

Some break words into syllables or even letters and combine separate numbers to form words phonetically or to partially spell them out–as say, if one were to break the word etait (was or were) into four: et-a-i-t, then it might look something like this when enciphered. 20.14.59.29. (As if in fact it did when found in a letter from one French officer…)

By the winter of 1811, amidst the confusion of too many code tables and who knew what and when, Napoleon had his chief fixer in Paris, Hugues Maret, compose a new cipher which was to be sent out to all the Marshals in Spain and Portugal and to King Joseph too. The table had 1200 code numbers, which was expanded to include another 200 numbers which mainly described Spanish places or terms.

The new more complex code, le Grand Chiffre, or the Great Paris Cipher as it was now called, allowed for the same words to be broken up and encrypted in several different ways–making it nearly impossible for a British code-breaker to crack the thing.

The new more complex code, le Grand Chiffre, or the Great Paris Cipher as it was now called, allowed for the same words to be broken up and encrypted in several different ways–making it nearly impossible for a British code-breaker to crack the thing.

Thus the sentence (this is from an actual letter), “Ah my friend, he could not disguise that he was the cause of the capture of [Ciudad] Rodrigo” looked like this when encrypted, “Ah my friend, he could not disguise that he 20.14.59.29 the 36.49.1.12.63.14.17 of 6.28 27.30.31.21.17.41.40.30.49.10.41.39.31.43.10”.

You can imagine the rolling of eyes in the British camp when they came across this stuff…But, as the guerrillas were picking off French couriers with the same ease as shooting fish in a barrel, any and all French messages between Napoleon and his cohorts were written using this code–so you might say, there were nothing but coded letters.

Anyway, despite the challenge or perhaps because of it, a rather canny and quite tenacious fellow by the name of George Scovell didn’t roll his eyes and give up, he cracked the Frenchie blighter!

Anyway, despite the challenge or perhaps because of it, a rather canny and quite tenacious fellow by the name of George Scovell didn’t roll his eyes and give up, he cracked the Frenchie blighter!

It didn’t happen all at once and he wasn’t alone in working at it. Copies of the encoded messages captured by guerrillas were sent on by Wellington to the Foreign Office, the War Office and Horse Guards in London, and their home-grown boffins were hard at work on it too.

[A word about the decrypting process: the code-breaker’s eye naturally seeks out the repetitive sequences or particular numbers. For example, the letter e is the most commonly used letter in English. It also occurs quite frequently in French and Spanish, as does u. So, the genius of the Great Paris Code is that they didn’t just use numbers for single letters, they also used bigrams and/or whole word codes. Which makes it almost impossible for the code-breaker to develop a rule.

By having the endings of French plural verbs encoded–that’s ons, ez and ent–again, they’re making it more difficult to establish the rules as the cryptographer might spell the letters out using numbers for each letter, or they might vary that with numbers to represent the verb endings. So a code-breaker can never be sure where the words begin or end–it’s just this fiendish stream of numbers across the page.

And the big break didn’t come until the French in the field began to get sloppy and write enough of their letters en clair that Scovell and the others could deduce the encoded words from the context within the sentence.]

But Scovell, because he had greater access to all the incoming captured communications, and because of his hard work, fine brain and excellent French, was the man to crack the thing wide open–and this without the help of Alan Turing or a prototype Enigma computer…

But it was that huge.

For decrypting the Grand Chiffre enabled Wellington and the British troops to outflank and outmanoeuvre the French, even as Napoleon was withdrawing 30,000 of the best of them for his campaign against Russia…

I don’t know how long it took–but the French didn’t learn for the longest time that the Grand Chiffre had been virtually decoded and that the British knew in advance what they were likely to be up to and were responding accordingly. Possibly by the time they worked that out, it was too late–Joseph was abandoning Madrid, Wellington had the French on the run…And this is about at the same time as Napoleon is invading Russia–so just prior to writing the abovementioned letter in code, which as you’ve seen, was hardly a singular event… (punk)

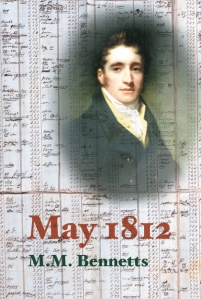

(And yes, the reason I learned all this stuff, including how to crack these coded messages, was so that I could put it in my novel, May 1812…right at the beginning. And yes, there on the cover of the book is a page from Scovell’s decryption table, now found in the National Archive.)

I read a biography of Scovell some time ago — also to learn about codes for a book, but the Grand Chiffre was way too elaborate for my purposes. Fascinating stuff, though.

[…] Napoleonic codes […]

Wonderful post! I’ve decided that I must have been a spy in at least one of my past lives as anything to do with codes and spying has my immediate and unblinking interest. Another reason I so love your books. 😉

Glad you approve. *wink* I can break these kinds of codes, ones that require a great knowledge of the language and one where my eye is always seeking out legnth of word and letter clues, but I would have been useless on the Enigma…

More and more spies in the next book. *happy face*

Scovell = Stephen Maturin? 🙂

I think Maturin was a composite. The Foreign Office were well-up in code-breakers. So was the Irish Office under Sir Charles Flint. There was the black chamber in the Post Office where they opened all foreign mail–incoming or outgoing–and copied it. And there are several other men–all of them spies–who travelled extensively thoughout the war.

Hi again MM

I’ve been reading the book you suggested to me a while back on one of your other posts – “The Man who Broke Napoleon’s Codes”. Absolutely fascinating book!!

I was wondering if you knew if there is a copy online of the fully decrypted Grande Chiffre that Napoleon used for Joseph?

Many thanks!

Dave

PS My wife thoroughly enjoyed “May 1812”!

As far as I know there isn’t a copy online of the decrypted Grande Chiffre, although that doesn’t mean there won’t be. The image of the George Scovell pages that were used on the cover of May 1812 were from the National Archive, which houses them.

Delighted that May 1812 went down well. Makes my day, that does.