(‘Struth, I am so chuffed about this!)

Ehem. Well, since I do not know absolutely everything–one does one’s poor best but inevitably there are gaps–I thought I should engage a proper expert in all things swordsmanlike to cover this aspect of Georgian and Napoleonic life.

Because swordsmanship, like horsemanship, is one of those common features of the age which so many writers think they can cover without every getting up close and personal–either to the steel or the muck. And it just doesn’t work that way. So without further ado, may I introduce Mr. Terry Kroenung, an absolute top o’ the trees swordsman and theatrical fight choreographer, an expert with all things steely…

“He Cut Him Dead”

Small-sword Duelling in the Napoleonic Era, Part One

A couple of centuries ago there was rather less unfriending on Facebook than one sees nowadays.

Even if such technology had existed in 1805, simply ignoring an insult was not as popular amongst the aristocratic bloods of Georgian Britain as its alternative: transfixing him on thirty-odd inches of Sheffield steel as if he were a newly collected butterfly.

Even if such technology had existed in 1805, simply ignoring an insult was not as popular amongst the aristocratic bloods of Georgian Britain as its alternative: transfixing him on thirty-odd inches of Sheffield steel as if he were a newly collected butterfly.

For a myriad of reasons (chiefly the caution-dampening effect of testosterone) the gentlemen of that age were quick to take offense. Granted, by the early 19th century pistols had largely replaced swords as the weapon of choice, but this essay is restricted to affairs of honour settled with the blade.

That item was most often what we now term the small-sword or court sword, a wicked wasp’s-sting of a thing, perhaps the best close-combat weapon ever designed. It weighed no more than a pound (an Elizabethan rapier weighs more than thrice that), boasted a speed and balance without peer, and could be thrust with ease completely through a human body.

That item was most often what we now term the small-sword or court sword, a wicked wasp’s-sting of a thing, perhaps the best close-combat weapon ever designed. It weighed no more than a pound (an Elizabethan rapier weighs more than thrice that), boasted a speed and balance without peer, and could be thrust with ease completely through a human body.

The lack of mass is deceptive. Triangular in cross-section and hollow-ground (much like a modern sport epee, only somewhat larger), the blade is very strong for its weight and given the proper temper, can bend nearly to the hilt and return to true. Almost entirely a thrusting tool, since this permitted penetration of vital organs rather than more superficial cuts to the foe’s integument, it would still have had a sharp enough edge to dissuade an opponent from attempting to grab the blade in defence.

Protection for the user’s hand would be minimal, often consisting of only one or two coquilles (shell-shaped plates) across the fingers. Most had a delicate knuckle bow as well.

No war weapon this, but a civilian one of great utility and beauty, worn just as often as a fashion accessory as for legitimate defence. And quite legitimate it was. There was a perfectly sound reason for the preference of most duellists for gunpowder.

No war weapon this, but a civilian one of great utility and beauty, worn just as often as a fashion accessory as for legitimate defence. And quite legitimate it was. There was a perfectly sound reason for the preference of most duellists for gunpowder.

A small-sword is more lethal than a pistol.

Consider: the inaccuracy of a smoothbore flintlock pistol at a distance of over thirty feet, while often overstated, is considerable. In addition, it only fires once.

A small-sword can be thrust three times per second at the closest of ranges and is “loaded” for as long as its wielder has strength in his arm. The fatality rate for pistol duels was only 6.5%. In sword exchanges fully 20% died.

As evidence of the horrific carnage involved in a small-sword exchange, I give you the 1712 Hyde Park encounter between the Duke of Hamilton and Baron Mohun (the latter’s father was killed in a duel, incidentally…or perhaps not so).

A callous murderer who richly got what he deserved – he died in a ditch — Mohun took a sword thrust completely through his torso from right ribs to left hip and a fatal severing of the right femoral artery. Three fingers of his off-hand were nearly severed from seizing his opponent’s blade.

Poor victorious Hamilton was dispatched by Mohun’s second as he stood over the mortally-wounded man. He bled out through the brachial artery of his upper arm while also being penetrated diagonally downward through the chest to a depth of eight inches. Mind you, these are merely the primary wounds. Both men had many others, as neither bothered any defensive manoeuvres (more on this later) save grasping the foe’s steel.

Then there was the 1772 affair between the famed playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan and Captain Thomas Matthews. Both blades broke and the fight essentially became a dagger fray. To quote from a contemporary account, Sheridan was “borne from the field with a portion of his antagonist’s weapon sticking through an ear, his breast-bone touched, his whole body covered with wounds and blood, and his face nearly beaten to jelly with the hilt of Matthews’ sword.”

Small wonder that pistols were preferred.

Our small-sword was no egalitarian device. A major reason for Napoleonic-era duels being primarily with pistols is that by that time the sword was no longer commonly used for personal defence in the street. (One suspects that lawyers were beginning to replace it.)

Blades required years to master, while a handgun’s basic techniques could be learned in minutes. A typical gentleman did train in swordplay (it was taught at Eton among the auxiliary lessons) but the need for it no longer arose so often as in Shakespeare’s day. Those who were adept in sword fighting had an advantage over the majority who did not. So shooting, an easier talent to acquire, became the equaliser.

Fencing skills were still being taught, of course, most notably in the salle of Domenico Angelo, an Italian master schooled in the French style of swordplay. He trained the upper levels of the British aristocracy (George III and IV among them) in fencing more as a matter of gentlemanly deportment than as a means of fighting duels. One learned to use a foil much as one learned to ride or dance. Fencing became more of a sport than a life-saving talent, though there were many who attended Angelo’s lessons for both reasons.

Fencing skills were still being taught, of course, most notably in the salle of Domenico Angelo, an Italian master schooled in the French style of swordplay. He trained the upper levels of the British aristocracy (George III and IV among them) in fencing more as a matter of gentlemanly deportment than as a means of fighting duels. One learned to use a foil much as one learned to ride or dance. Fencing became more of a sport than a life-saving talent, though there were many who attended Angelo’s lessons for both reasons.

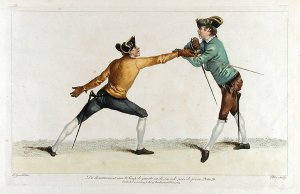

Contemporary images show well-dressed men in the tight breeches and waistcoats of the age, at Angelo’s salon overlooking Soho Square, elegantly thrusting at one another sans masks. Such protective devices did exist, in an early and crude form, but were often scorned as intimating that one could not trust his partner’s point control.

Contemporary images show well-dressed men in the tight breeches and waistcoats of the age, at Angelo’s salon overlooking Soho Square, elegantly thrusting at one another sans masks. Such protective devices did exist, in an early and crude form, but were often scorned as intimating that one could not trust his partner’s point control.

One could be excused for believing that such fine technique, such masterful control of one’s point, such perfect form while delivering thrusts, coupes, and glissades, would be the norm in any duel between true gentlemen.

Alas, we have already seen the truth a la Mohun and Sheridan.

Posted a link on FB because others should realise swordplay’s not all that’s it’s cracked up to be. Especially if you’re the one on the receiving end.

No. I’ve been even thinking I should do a piece on just how dangerous and violent London was circa 1812. I get the sense that many people think it was all a nice West End neighbourhood by then. The reality couldn’t be further from the truth. One went out armed because one was likely to need to defend oneself.

Fascinating post from TK. I took advice from a modern-day maitre, who introduced me to the skill on a beach one Christmas morn. The post reminded me of The Duellists, which I must watch once more.

A favourite film of mine too, that. Another with fine Napoleonic duelling is…well, it goest by several names…here, I think it’s called All for Love. In the US I think it may be called St. Ives. It’s from a Robert Louis Stevenson story and features an excellent cast including Jean-Marc Barre, Miranda Richardson and Richard E. Grant.

I find this sort of thing fascinating. Thank you, Terry – and M

Great insights here, TK… And MM could not have picked a more knowledgeable expert on the subject of gutting ones opponent. I’m off to read part two.

Part 2 is even snarkier, but then, it would be, wouldn’t it? 😀

The form matches the content–wonderful telling of this peculiar pastime, thanks Terry.

[…] The Art of the Duel or Killing Each Other Like Civilised Human Beings and Gentlemen… […]

I *love* the French small sword picture; a nice bit of kit. I know one of two Gin Lane gents who would be happy to wield it.